Routing the routeing plan

Page 31

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Brian Cottee

LONDON'S ABANDONMENT of its designated lorry route network is the tip of a national iceberg. Transport Minister John Gilbert hinted at the situation when, opening CM'S Fleet Management Conference in September, he made it clear that he was taking a very cautious line on designated lorry routes, but equally was preparing new plans to deal stringently with noise and smoke emissions from vehicles.

Both on the national plan for lorry routes and on local routeing networks, the authorities have been discovering the truth of warnings that without extensive new road building, lorry routes will simply concentrate heavy traffic flows into inadequate roads.

Residents, actively encouraged by environmental groups, have given London's 425-mile designated lorry network an enormous thumbs-down, As the GLC assistant chief freight planner, Martin Foulkes, revealed at the FTA national conference last week, the proposals drew an unprecedented 55,000 objections—compared with the 28,000 to the Greater London primary roads plan in 1969. Of the 55,000 lorry route objectors, over 42,000 signed organised petitions, but there were 12,410 from individuals, 280 from societies and groups and 66 from freight and trade interests.

In recent weeks the DoE has also made it clear that its original programme for national lorry routes was most unlikely to be achieved, while in the Commons last week Dr Gilbert told Hugh Dykes MP that local authorities were likely to concentrate their limited resources upon modest measures at " pinchpoints " and on banning heavy traffic from the "rat runs."

In the words of Martin Foulkes: " It seems increasingly likely that a simpler and more incremental approach will be adopted in which the distinction between main traffic routes and lorry routes is minimised and only represents a marginal factor."

In London, as elsewhere, the emphasis will now shift to banning heavy lorries from environmentally sensitive areas and operating advisory routes; for the foreseeable future, the designated lorry route looks a nonstarter.

Some of the reasons for this gentler approach to living with the lorry were spelt out by Mr Foulkes in his FTA paper. Although the noise, smoke, vibration, and safety aspects of the heavy lorry were a matter of concern, especially since the number of vehicles over 8 tons unladen in London had increased by over 80 per cent between 1962 and 1972, the GLC could not adopt policies which would damage industry. The Council was aware that London had to re-assert its competitive edge in economic terms. The drift of industry from London must not be exacerbated.

Most lorry route objectors had been in favour of an absolute ban on all vehicles over 16 tons gvw in London, said Mr Foulkes, but this would cost E100 million a year in extra operating and secondary costs and would require 13,000 extra drivers. Its effect on London's industry did not bear examination.

As a long-term aim, the GLC could exclude the really large vehicles from areas where they were not essential but allow them access to the industrial areas of London. In other areas vehicles over, say, 40ft would be admitted only by permits issued to industrial users who could show a case for using the big vehicle.

Mr Foulkes envisaged that enforcement would be at a low level to keep costs down, while industry would be encouraged to " drift " into those areas where big vehicles were allowed free access. He envisaged that it could take 10 years to implement the whole scheme.

The impossibility of meeting industrial and trade needs without road transport is made dramatically clear by the revelation that GLC planners have calculated that an increase of 50 per cent in rail and water freight carryings in London would cut road freight by only 5 per cent. The recent recession has probably reduced heavy lorry usage by 20 per cent in some areas—but has this been noticed by the public ?

As well as designated routes, the idea of a chain of transhipment depots seems also to have been abandoned. Mr Foulkes admitted that the idea of 10 local transhipment warehouses in London did not now look like an economic proposition and the only transhipment which is likely to develop is that which meets the commercial needs of the freight market.

So where does this leave freight restraint in London ?

Certainly there is going to be pressure for quieter, cleaner vehicles. Mr Foulkes suggested that this would be justifiable even if it meant 5 or 10 per cent on the cost price of the vehicles. When the options were few, even expensive solutions might have to be adopted. As an example, he suggested urban vehicles not exceeding 5 tons unladen or 16 tons gvw carrying a special plate to certify that they met a particular noise level.

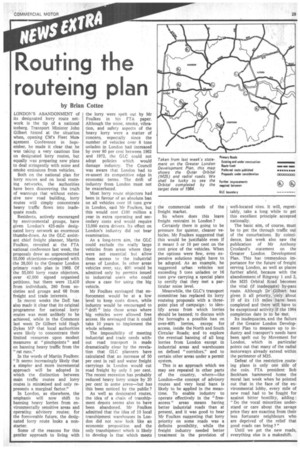

.Meanwhile, the GLC's transport committee has replaced its lorry routeing proposals with a threepoint plan of campaign: to identify areas from which lorries should be banned; to discuss with the boroughs a possible •ban on aver-40ft lorries, except for access, inside the North and South Circular Roads; and to explore the eventual banning of all long lorries from London except in industrial areas and warehouses on defined " corridors," and to certain other areas under a permit system.

This is an approach which we may see repeated in other parts of the country, where—like London—the concept of advisory routes and very local bans is likely to be applied in the meantime. To enable industry to operate effectively in the " freeaccess " areas means having better industrial roads than at present, and it was good to hear Mr Foulkes suggesting that lorry priority on some roads was a definite possibility, while the freight industry needed better treatment in the provision of well-located sites. It will, regrettably, take a long while to get this excellent principle accepted nationally.

The basic aim, of course, must be to get the through traffic out of the conurbations. By coincidence, last week also saw the publication of Mr Anthony Crosland's statement on the Greater London Development Plan. This has tremendous importance for the future of freight serving London, as well as places further afield, because with the abandonment of Ringway 1 and 2, the M25 Orbital Road becomes the vital (if inadequate) by-pass route. Although Dr Gilbert has given it all priority, only about 10 of its 115 miles have been completed and there will have to be exceptional activity if the 1984 completion date is to be met.

Its inadequacies, and the failure of the Greater London Development Plan to measure up to industry and transport's needs have been spelt out by Movement for London, which in particular points out that many of the radial motorways already extend within the perimeter of M25.

Defeat of the restrictive routeing plans is only one side of the coin. ETA president Bob Beckham hammered home the moral last week when he pointed out that in the face of the environmental lobby, every mile of new road had to be fought for against bitter hostility, adding : " Do the vocal minorities understand or care about the savage price they are exacting from their less fortunate neighbours who are deprived of the relief that good roads can bring ?"

Until we get the new roads, everything else is a makeshift.