AEROPLANE SERVICES.

Page 10

Page 11

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

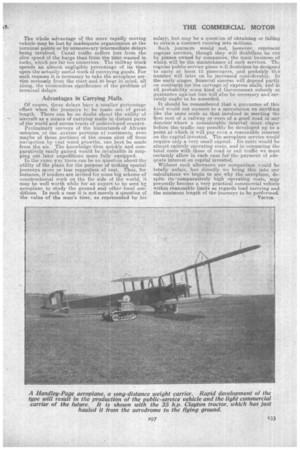

The Long-distance Public-service Vehicle and Light Commercial Carrier of the Future.

THERE ARE STILL PLENTY of people who will regard it as absurd to suggest classifying the aeroplane as a commercial vehicle, but these are probably the same people who, had they lived in other days, woeld have assured us that no steamship could ever cross the Atlantic and that no railway could ever compete successfully with the stage coach. People who possess imaginations are always liable to the ridicule of those who do not, and therefore, in a case of this kind, it behoves us to back our beliefs by something in the nature of solid argument.

Let us take the first objection urged against the aeroplane as a commercial or public-service vehicle. This is the high cost of operation, coupled with the danger of accident. The latter was equally urged a few years ago as a conelusive argument against the rooter omnibus, and, in yet earlier days. against the railway train. When the Great Western Railway was under construction, Members of Parliament seriously and volubly opposed proposals which involved the construction of a long tunnel on the grounds that the noise made by a. train in,passing through would be so terrifying that no passengers ;would venture aboard. Every new methoti..of transport is revarded as dangerous until it is proved safe, and the process of proof, so far as the aeroplane is Concerned, is making rapid headway.

• Operating Costs Not Unduly High.

Let us then turn to the question of operating costs. Experience shows us that comparatively high operat ing costs, in themselves, are not necessarily proof of complete inferiority of the method which mvolves them. We must, of course, consider not merely the cost per mile but the cost per passenger or ton-mile as the ease may be. In working out the details of an aerial service between London and Paris, Mr. Holt Thomas estimated the total cost per mile at 4s. 8c1., with the probability that with a regular service ip operation it could be reduced to 3s. a mile as a, safe

figure. Each machine would carry about 2500 lb., less petrol, oil and pilot. Taking the round figure of 2000 lb., accommodation would be provided for, say, twelve passengers, who would pay 25 each for the single journey.

Thus, if the full load of the passengers were always obtained, there would be a profit of 215 on each single trip. If the number of passengers fell short of the full complement, the profit at any rate would drop considerably and might easily turn into a loss. If we assumed an average of half load then, to make any profit at all, we should have to charge passengers about 28 apiece for the single journey (which works out at something over 6(1. a. mile).

The question of whether public services could be run at such rates is really dependent on the value of the potential passenger's time. The journey would certainly take not more than half the time occupied. in making it by express train and steamer. Conse quently, any man whose working time is worth any thing over about 21 an hour, might find it cheaper to travel by plane than by the usual method. The argu ment is just the same as that which unquestionably influences a great many people to move about by taxicab instead of by bus or on foot. Doubtless the habit is often due to laziness, but it is not BO in every case. If ten minutes can be saved on a journey betweene office and office, then an extra charge of 2s. ed. is justified if the traveller's time is worth 15s. an hour. Our whole system of passenger transport shows that there are always a fairnumber of people who are willing to pay, and who are justified in paying, a higher price for a quicker journey. This is an aspect of the transport problem whioli is too often forgotten. Even when differences of speed are inconsiderable they may have a distinct monetary value. For instance, the decision between the motorbus and the tram cannot rest entirely on operating costs, and saving of time is one of the factors that should, be taken into account in making a comparison. This saving is mainly due to the greater ability of the bus to select its own route within certain limits. These limits are nano* ones, since the bus service must always cover the same series of roads. The vehicle can, however, move from side to side of a, road at will, and so escape some of the hampering effect of other' traffic. The tram has neither the power of getting out of the way of other traffic nor the power of skirting round traffic which is in. its way.

Freedom From Traffic Obstructions.

In fact, every present organized method of transport is sooner or later affected by the presence of congestion along its route, and in this respect aerial services will have a permanent advantage which will become more and more important as traffic congestion upon the ground increases. Any appreciable congestion of traffic in the air is. beyond imagination, because the aeroplane is free to move in three dimensions and consequently the number of roads available to it is almost infinite.

The plane will, however, suffer to some extent from one of the other great difficulties always experienced by all other systems. This is the difficulty of terminal delays and delays en route, in the matter of terminal delays, the railways are the worst sinners, and their troubles are partly due to the feet that, in the early days, many peoPle would not appreciate the advantage of having railway stations placed in the most convenient positions. Many towns refused to have them within their boundries, with the result that they have since been obliged to grow towards and round their stations, which are still not central.

.A Mistake to Avoid.

There is a distinct danger that when we come to the planning of a comprehensive series of landing grounds for aeroplanes, we shall make the same mistake again. The main landing grounds for large cities should be situated as centrally as possible. We cannot realize the full advantage of high speed during the main journey if we have to spend a long time getting to the starting point and again in getting to our destination from the terminus.

In the matter of intermediate delays, the aeroplane has a great advantage, because it travels equally easily over land and over water :s Thus, a journey from one country to another separated from it by water does not involve delays in changing from train to boat and from boat to train. We shall need to remember that the saving of time due to this and other causes is one of the great arguments in favour of the aeroplane for the carriage of passengers and light goods, and we shall have to scheme to eliminate all terminal delays so far as it is possible to do so. It has been pointed out before now that, though the speed of a railway train is much greater than the practical speed of a motor van along the road, yet the carriage of goods from point to point by motorvan is often a much speedier operation than their conveyance by rail.

The whole advantage of the more rapidly moving vehicle may be lost by inadequate organization at the terminal points or by unnecessary intermediate delays being involved. Canal traffic suffers less from the slew speed of the barge than from the time wasted in locks, -which are far too numerous. The railway truck spends an almost negligible percentage of its time upon the actually useful work of conveying goods. For such reasons it is necessary to take the aeroplane service serioissly from the start and. tti bear in mind, all along, the tremendous significance of the problem of terminal delays.

Advantages in Carrying Mai1..

Of course, these delays have a smaller percentage effect when the jonrue,ys to be made are of great length. There can be no doubt about the utility of aircraft as a means of carrying mails to distant parts of the world and across tracts of undeveloped country.

Preliminary surveys of the hinterlands ofAfrican colonies, of the interior portions oi continents, even maybe of those portions of the ocean shut off from navigation by vast weed, growths, can best be made from the air. The knowledge thus quickly and comparatively easily gained would be invaluable in mapping out later expeditions more fully equipped.

In the same way there can be no question about the utility of the plane for the purpose of making special journeys more or less regardless of cost. Thus, for instance, if tenders are invited for some big scheme of constructional work on the far side of the world, it may be well worth while for an expert to be sent by aeroplane to study the ground and other local conditions. In such a case it is not merely a question of the value of the man's time, as represented by his salary, but may be a queStion of obtaining or failing to obtain a contract running into millions.

. Such journeys would . not, however, represent regular services, though they will doubtless be run by planes owned by companies, the main business of which will be the maintenance of such services. The regular public service plane will doubtless be designed to carry at least 12 passengers, and probably tb.s number will later on be increased considerably. In the early stages, financial success will depend partly on contracts for the carriage of express niails, and in all probability some kind of Government subsidy or guarantee against loss will also be necessary and certainly ought to be. accorded.

It should be remembered that a guarantee of this kind would not amount. to a speculation on anything like the same scale as that involved in meeting the first cost of a railway or even of a good road in any district where a• considerable interval must elapse before the traffic can possibly be developed up to a point at which it will pay even a reasonable interest on the capital invested. The aeroplane service wotild require only a very small capital. Its costs would be almoSt entirely operating costs, and in comparing the total -coats with those of road or rail traffic we must certainly allow in each case for'the -payment of adequate interest on capital invested.

Without such allowance our comparison would be. totally unfair, but directly we bring this into our calculations we begin to see why the aeroplane, despite its comparatively high operating costs, may presently become a very practical commercial vehicle within reasonable limits as regards load carrying and the minimum length of the journeys to be performed.