eggett Freightways pecifies the eight ylinder Gardner for its nnnatched

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

durability — 00,000km without ttention. But the utstanding feature of he turbocharged in-line ight around CM's ;cottish route was its Jel economy : a new tandard for 38 tonnes cw DESPITE the hampering uncertainty which for so long has surrounded the maximum weight uplift, there has been a clear trend in the past few years for operators of maximum weight tractive units to move up the horsepower scale. 270-300hp had become the most popular category long before Parliament put the industry out of its misery with confirmation that 38 tonnes was to be the new limit.

Until mid 1982, though, the most powerful automotive engine that the Hawker Siddeley group's L. Gardner and Sons of Manchester had on offer was the 265hp naturally aspirated straight eight, 8LXC, and its market share in the premium tractive unit sector was tumbling.

The turbocharged version of this engine which was unveiled last year represents a serious attempt by Gardner to win back its lost market-share.

The fact that the increased weight limit has become effective virtually concurrently with production of the 8LXCT coming on stream can only be good news for the company, which despite recent setbacks, remains Britain's biggest home market supplier of automotive engines above 180hp, when truck and bus applications are taken into account.

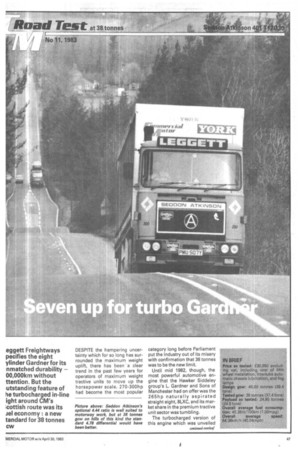

The engine driving this week's test vehicle was the first production 8LXCT. The 401 to which it was fitted went into service with Leggett Freightways of Chingford, Essex, last November and at the start of our operational trial had completed some 69,000km (43,000 miles) on double-shifted trunking work between London and Manchester.

Leggett's fleet engineer, John Linney, reports that the engine has been problem-free to date and its average fuel consumption pulling 4.4m (14ft 6in) high box semi-trailers and at a gcw generally of 32.5 tonnes has been a very healthy 36.2 lit/100km (7.8mpg).

Our trial of the 8LXCT 401 was at 38 tonnes gcw with our new York tri-axle, curtainsided test trailer. The interior height of the trailer has been kept relatively low at 2,285mm (7ft Gin) so that the results of future 38-tonne tests will be comparable with those of the seven we have already run with the Al tilt.

As the results page shows, the Gardner-powered 401 set a fuel consumption record around the Scottish route, using less diesel than any other 38-tonner we have tested so far (apart from the Mercedes-Benz 1638 which put up a remarkable performance but cannot fairly be compared with the others because it was pulling a special low-height, streamlined, German semitrailer).

Volvo's F12 (tested CM, March 13, 1982) was the previous most frugal 38-tonner tested but the Seddon Atkinson's overall average mpg was better by a clear margin. However, surprisingly, the Gardner was not consistent in its fuel economy, starting off for example extremely impressively with over 8mpg on the mixed A-road/motorway section between Nuneaton and Burton service area but then inexplicably falling back to 6.68mpg over the next stage which though marginally more demanding does not usually cause fuel consumption to fall so markedly.

And then on the relatively easy, gently undulating terrain of the A74, the best the Seddon Atkinson could achieve was 6.92mpg while the Volvo scored an impressive 8.20mpg, the Rolls-Royce 290L powered 401 (May 22, 1982) bettered 8mpg, and between 7 and 8mpg from 38 tonners over this section is commonplace.

Certainly the gearing of this 401 was far from ideal for running at the 40mph limit. Seddon Atkinson's engineers had con sidered changing the rear axle ratio for the test from the 4.44:1 specified by Leggett to the standard 4,7:1, but Gardner was confident that the 8LXCT would pull the taller gearing at 38 tonnes and argued in favour of the motorway economy to which it should lead.

That it undoubtedly did with only 1,650rpm on the tachometer when the tachograph was indicating 60mph, but at 40mph the choice was between eighth (direct) at 1,500rpm or ninth at 1,100rpm so even slight gradients demanded a down change.

I am inclined to think that for general work in this country at 38 tonnes, the higher (numerical) ratio of 4.78 is preferable behind the 8LXCT. On several gradients during the test the nine-speed Fuller's ratio steps were just a little too wide (up to 38 per cent between 5 and 6) leaving the Gardner caught between gears. This is despite its excellent flexibility, which results from a torque output that drops from the maximum ol 1,173Nm (865 lbft) no more than four per cent between 1,000rpm and the full power speed ol 1,90Orpm.

Leggett's preferred solution is to keep the longer-geared axle, which it also has specified in the naturally aspirated Gardnerpowered 401s in the fleet, and fit a 13-speed Fuller gearbox tc give smaller ratio steps in higt. range. Our test vehicle waE going to be fitted with a 13speed Roadranger before it re joined the Leggett international fleet running to Switzer land, Holland and Germany.

It is interesting to note, however, that the RTO 9512 equipped lveco 170.30, with a similar capacity engine to thE Gardner (though with more pea) power and torque), and broad1.11 similar overall gearing, coulc better only one of this Seddor Atkinson's hiliclimb times, anc could not improve on speed and fue consumption.

One factor which must have had some adverse effect on thl Gardner's motorway perform ance was a tendency to "hunt' at about three-quarter throttli setting, which occasionally made it difficult to hold a steady 60mph. I later learned that this was caused by over-zealous tightening of the timing chain immediately prior to the test — rather ironic really, because it is usually neglect of the timingchain tension which causes one of the few Gardner in service problems.

And just like the 8LXC I drove last year (401 test 27.3.82), the accelerator pedal return spring on this vehicle was too strong — making it uncomfortable to hold down the pedal for long periods.

The only way Gardner could overcome this would be to change the design of its mechanical governor and that the company is understandably reluctant to do.

The 8LXCT is reported to be a "clean" engine with combustion having been improved, even compared with the high standards of the 8LXC and certainly when the engine was hot there was no trace of exhaust smoke. But starting from cold was a very different matter with dense white clouds of smoke accompa nying the rather reluctant cold sl:art. This characteristic is a direct result of the Gardner's low compression ratio and again the manufacturer is not willing to jeopardise durability for the sake of easier cold starting.

My only other criticism of the engine is that it lacks an exhaust brake, a component which is even more useful at 38 than at 32 tonnes gcw, for controlling speed on gentle down gradients. I understand that a Gardner-approved exhaust brake might become available in the future.

In other respects the braking cf the Seddon Atkinson/York 38 tonnes combination was exemplary, with the rolling road test showing high efficiencies and good balance between axles while the dynamic track braking tests revealed no imbalance or wheel locking.

As for the tractive unit's ride and handling, my impression was that this Seddon Atkinson at 38 tonnes rolled rather more on roundabouts than I would expect at 32 tons, but never enough to cause concern, while the well-laden parabolic springs at front and rear gave a firm ride with little unpleasant fore and aft pitching.

The intermittent rain during the test highlighted three failings on this 401: mirrors which foul up very quickly (as happens on all 401s in the wet), a leaking roof at the header rail joint which has been a recurrent 401 problem but is now reported to be cured, and a wiper relay which could be persuaded to work properly only by occasional sharp blows.

Summary John Linney does not specify Gardner eight-cylinder engines solely for their good fuel economy. With the intensive double-shifted, high-mileage trunking they are used on, he is more concerned with how relia ble and durable the engines (and indeed the complete vehicles) will be, rather than with how little fuel they use, though of course good fuel economy is welcome.

No other engine that Leggett has tried can stand the tough pace of the operation so well as the eight-cylinder, naturally-asp i rated Gardner, and now 600,000km (373,000 miles) is expected from each engine without a spanner being laid on it, except for routine maintenance.

There is no reason to suppose that the turbocharged eight will be any less reliable than its predecessor for the boost pressure of the single turbocharger (preferred by Gardner for its simplicity to the twin turbocharger considered in the early stages of development) is low so that mean effective pressures have been increased by only 15 per cent.

This operational trial showed the 8LXCT-powered 401 to be capable of averaging around 7.00mpg at 38 tonnes gcw over a wide variety of UK roads and at a respectable, though far from swift, average speed.

With a 13-speed gearbox and/ or slightly different overall gearing, the results might be even more impressive, but the manufacturer of any vehicle that could better this Seddon Atkinson's performance would be well satisfied.