THE REAR-ENGINED CHASSIS—

Page 94

Page 95

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

will it benefit the goods-vehicle operator?

WIILLST much attention has been given to the matter of rear-engine installations for passenger vehicles, the desirability and practicability of similarly accommodating the power unit in goods chassis has received comparatively little consideratiot.

It might be contended that the common practice of positioning the engine beside the driver minimizes sufficiently the encroachment of this component upon useful space. In contravention of this argument, however, is the fact that, if it be worth while to build a goods compartment over the driver's head, the space. at his side must be equally, if not more, useful.

In addition, if the radiator be kept below floor level and the panelling at the front be detachable or hinged, long loads can be placed on the floor with their ends projecting at both back and front. That is a much better arrangement than letting them stick out only at the rear for possibly a third of their length.

Uninterrupted Loading Area.

Provided that an engine of suitable type be etnployed, and that it be accommodated below frame level, then the platform is clear for its whole area, except where the driver's seat, enclosure and controls are mounted. However, even if the engine be of orthodox design and of a height too great for the above provision, there yet remain certain important advantages that do not obtain with a forward or central power installation.

Chief of these is the low loading line amidships that becomes possible. Given that there is no mechanism forward of the rear axle—no gearbox or propeller shaft—the platform can be brought down to a height determined only by the means required for its support and the necessary ground clearance. Moreover, if independent front-wheel suspension be employed, this low level may continue to the extreme front.

Even when a normal front axle be used, provided that this is well dropped, the level at the front need not be much greater than that amidships.

The need for a low platform does not always exist; nevertheless, there can be few circumstances in which a practically uninterrupted loading area is not an asset. This is, to all intents and purposes, impossible with a forward engine. There is, however, ample space for a horizontal engine under the floor between the road wheels. From the weight-distribution viewpoint that is the ideal place for it. What are the reasons for preferring a position behind the driving axle?'

The answer to this question may be found by investigating the matter of accessibility. Mounted at the rear, the unit can be reached from both sides and from the back, also, if floorboards be removed, from above. When centrally mounted, only the first and last apply.

That is not all. When it is required to remove the engine from the frame, it is far easier to shift it rearwards than to lower it and draw it out sideways.

Propeller-shaft Angularity.

One big difficulty arising when the engine is placed in close proximity to the driving axle, is that of providing for relative vertical motion between the two components. The shortness of the propeller shaft results in a higher degree of angularity, than universal joints of orthodox design are capable of affording—that is without excessive variation in angular velocity. This is not an insuperable obstacle, for joints well capable of functioning satisfactorily under the most arduous conditions of this nature are obtainable. Their incorporation, however, is bound to increase the cost of the chassis.

For vehicles intended exclusively for trunk-route work, provision for this relative motion might almost be dispensed with. With modern smooth roads and large lowpressure tyres with which wheels are now commonly shod, the unsprung parts have a much easier time than in the past. Accordingly, the engine gearbox unit might be bolted rigidly to the axle casing with its other end spherically jointed to the frame.

Such practice, however, limits the field of utility of the machine, and the better method is to follow more nearly the lines dictated by the conventional practice of to-day.

Yarious layouts for rear-eegined machines—in the main for passenger carrying—have been sug c36 gested in this paper from time to time, and we are reproducing on these pages sketches of some of the ideas that have appeared.

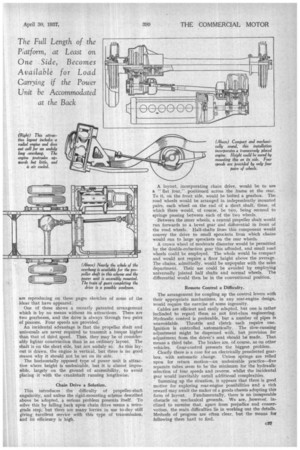

One of these shows a recently patented arrangement which is by no means without its attractions. There are two gearboxes, and the drive is always through two pairs of pinions. Four speeds are provided.

An incidental advantage is that the propeller shaft and universals are never required to transmit a torque higher than that of third speed. Thus, they may be of considerably lighter construction than in an ordinary layout. The shaft is on the short side, but not unduly so. As this layout is drawn, the engine is vertical, but there is no good reason why it should not be set on its side.

The horizontally opposed type of power unit is attractive where height is undesirable, but it is almost impossible, largely on the ground of accessibility, to avoid placing it with the crankshaft running lengthwise.

Chain Drive a Solution.

This introduces the difficulty of propeller-shaft angularity, and unless the rigid-mounting scheme described above be adopted, a serious problem presents itself. To solve this by falling back upon chain drive seems a retrograde step, but there are many lorries in use to-day still giving excellent service with this type of transmission, and its efficiency is high. A layout, incorporating chain drive, would be to use a " flat four," positioned across the frame at the rear. To it, on the front side, would be bolted a gearbox. The road wheels would be arranged in independently mounted pairs, each wheel on the end of a short shaft, these, of which there would, of course, be two, being secured to springs passing between each of the two wheels,

• Between the inner wheels, a central propeller shaft would run forwards to a bevel gear and differential in front of the road wheels. Half-shafts from this component would convey the drive to small sprockets from which chains would run to large sprockets on the rear wheels.

A crown wheel of moderate diameter would be permitted by the double-reduction gear this afforded, and small road wheels could be employed. The whole would be compact and would not require a floor height above the average. The chains, admittedly, would be unpopular with the sales department. Their use could be avoided by employing universally jointed half shafts and normal wheels. The differential would then be in the conventional position.

Remote Control a Difficulty.

The arrangement for coupling up the control levers with their appropriate mechanisms, in any rear-engine design, would require the exercise of some ingenuity.

Cables are efficient and easily adapted, but one is rather inclinded to regard them as not first-class engineering. Hydraulic control is preferable, but a number of pipes is unavoidable. Throttle and clutch each require one. Ignition is cobtrolled . automatically. The slow-running adjustment might be dispensed with, but provision for adjustment from the driver's seat should be made. That means a third tube. The brakes are, of course, as on other vehicles. Gear-control presents the biggest problem.

Clearly there is a case for an electrically preselected gearbox, with automatic change. Unless springs are relied upon for return motion—an undesirable practice—five separate tubes seem to be the minimum for the hydraulic selection of four speeds and reverse, whilst the incidental gear would inevitably entail additional complexities.

Summing up the situation, it appears that there is good motive for exploring rear-engine possibilities and a rich reward may await the maker of a goods chassis adopting this form of layout. Fundamentally, there is no insuperable obstacle on mechanical grounds. We are, _however, inclined to surmise that, apart from prejudice and conservatism, the main difficulties lie in working out the details. Methods of progress are often clear, but • the means for following them hard to find.