( From the 0i - skiing prpffi e

Page 16

Page 17

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Graham Montgomerie continues his series for engineers with further exploration of cab design. He comes down in favour compromise in weight-saving construction techniques.

IN THE last article in this series I touched upon the basic aerodynamic requirements of a heavy lorry cab and the relationship of these requirements to those of safety and visibility. Following on from this, I have been talking to Merrick Taylor and Neville 'O'Keefe of Motor Panels (Coventry) Ltd on how they see the cab designs developing in the next few years.

As cabs get more sophisticated in terms of driver comfort and noise insulation, so the weight goes up. The weight of a cab is a very critical factor in the production stage, let alone in the operational stage when it is fitted to a chassis. Obviously a heavier cab means less payload within the set gross weight limits but it also means more raw material and more energy expended in material handling in the production shop.

But it is easy to go overboard and get into a panic about weight. It is very easy to design an ultra-light cab using exotic materials but when it costs ten times as much as a "conventional" cab, then the purpose of the exercise has become somewhat distorted. As with everything else in the field of engineering, a compromise must be sought.

As the Motor Panels people told me, the right approach to _go for is a combination of materials — steel where steel is best, aluminium where aluminium is best and so on. Aluminium does have disadvantages as it is very expensive and the capital investment in plant needed to handle it is high.

This is an area where the _ . _ .

American manufacturers have been active for years. Not only is aluminium used for cabs, but also for frames and axles. The White Road Commander 2 on show at this year's Motor Show was a good example of this. It had a kerb weight of around six ,tonnes — impressive for a three-axle tractive unit with a sleeper cab.

Manufacturers have been coming under increasing pressure not only to reduce weight in this area but also to improve corrosion resistance, so alternative materials to steel have to be considered. Personally I still think that steel is likely to remain the most economical material for volume cabs (5,000 units per year and above) for the next ten years at least.

One of the major hold-ups to the large-scale production of an aluminium cab has been the need to develop a common technique to produce cabs in steel or aluminium. This is especially true of welding. Motor Panels is aiming to develop a method by which spot welding guns can be switched from aluminium to steel and back again at the flick of a switch, despite the differing power requirements of the two materials.

Merrick Taylor, Motor Panels' managing director, feels that the carbon fibre cab is a very long way ahead, if it happens at all. Future material developments will probably concentrate on coated steels and different steel /aluminium alloys.

Another material to be used for cabs is of course plastics in one form or another. ERF is a good example of a current plastics cab with its SP where the structural strength comes from a steel sub-frame and the outer shell is made from pre-formed SMC (sheet moulded compound) panels which are hot pressed in matching dies.

Personally I feel that SMC is going to be used more often in the future for non-load-bearing areas because of its resistance to corrosion. For structural requirements, steel is still necessary to meet the EEC impact recommendations. At this point I shall explain just what the cab must be capable of.

Impact Testing

The test procedure for frontal impact is straightforward a weight is swung at the front of the cab. Clearly, for uniformity of test results, the size and weight of the swing-bob and the dimensions of its arc of swing are rigidly controlled. Before the tests, the doors of the cab should be closed but not locked. For the frontal impact test, the cab has to be mounted on a chassis and an engine fitted, it is not essential that an exact production engine be fitted — merely one equivalent in weight, dimensions and engine mounting points. For the static roof-load test and the rear impact test, the manufacturer has the choice of mounting the cab on a chassis or on a separate frame.

The swing-bob for the frontal impact test must be of steel, with its mass evenly distributed. Its striking surface is required to be rectangular and flat with dimensions of 2.5m (8ft 21/2in) in width and 0.8m (2ft 71/2in) in height. The edges of the swingbob are rounded to a radius of curvature of not less than 1 .5mm (0.6in),while the weight has a tolerance of 250kg (550Ib) on either side of 1 .5 tonnes (1 ton 91/2 cwt).

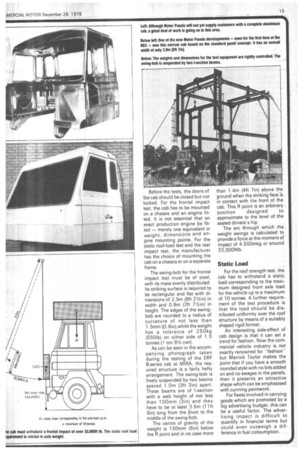

As can be seen in the accompanying photograph taken during the testing of the ERF B-series cab at MIRA, the required structure is a fairly hefty arrangement. The swing-bob is freely suspended by two beams spaced 1.0m (3ft 3m) apart. These beams are of I-section with a web height of not less than 100mm (3in) and they have to be at least 3.5m (11ft 61n) long from the ivot to the middle of the swing-bob.

The centre of gravity of the weight is 150mm (6in) below the R point and in no case more than 1.4m (4ft 71n) above the ground when the striking face is in contact with the front of the cab. This R point is an arbitrary.

position designed to. approximate to the level of the seated drivers's hip, The arc through which the weight swings is calculated to provide a force at the moment of impact of 4.500mkg or around 33,000ftlb.

Static Load For the roof strength test, the cab has to withstand a static load corresponding to the maximum designed front axle load for the vehicle up to a maximum of 10 tonnes. A further requirement of the test procedure is that the load should be distributed uniformly over the roof structure by means of a suitably shaped rigid former.

An interesting side-effect of cab design is that it can set a trend for fashion. Now the commercial vehicle industry is not exactly renowned for "fashion" but Merrick Taylor makes the point that if you have a smooth rounded style with no bits added on and no swages in the panels, then it presents an attractive shape which can be emphasised with cunning paintwork.

For fleets involved in carrying goods which are promoted by a big advertising budget, this can be a useful factor. The advertising impact is difficult to quantify in financial terms but could even outweigh a difference in fuel consumption.