GAS COACH SHOWS IT METTLE ON THE ROAD

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

WHEN manufacturers of passenger vehicles began installing oil engines in their chassis and when enterprising operators first used these prime-movers for p.s.v. work, they had to educate their patrons to the new•

conditions. There were noise and vibration, smell and smoke, breakdown and delay, whilst against the big saving in fuel cost, there was the high price of the more economical unit. Memories, however, fade so quickly that the thorn paths trod by the pioneers of those days—champions of the oil engine and prominent among whom was " The Commercial Motor "—are already three-quarters forgotten.

• We distinctly recall, nevertheless, writing on more than one occasion towards the latter days of the era we have in mind such words as these: " It was virtually impossible for an observer in the saloon to detect any differences between the running of this oil-engined coach and that of a like petrol vehicle.!'

To-day that sort of thing seems almost laughable. Keen perceptiveness is needed for experienced and expert faculties to tell what kind of engine is propelling the vehicle in which their possessors happen to be travelling at the time.

Now history appears to be repeating itself, but for oil we must substitute producer gas. We are passing through a period of development that is comparable, in many respects, with that in which the oil engine was struggling for recognition. Dare we hazard that this latest source of power may ultimately become equally well established in road-transport fields?

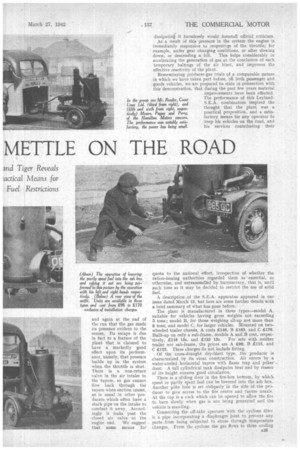

Only a week or two ago, during a demonstration run in a coach operating on producer gas, we heard—and agreed with—the very remark quoted above. Throughout that trip nothing made evident the fact that solid fuel instead of liquid fuel was being employed, except a slight falling off in the speed up relatively gentle gradients, and a smell of gas escaping from the carburetter air intake, immediately after switching off the engine. The latter was not apparent inside the coach.

The plant, on this occasion, was an S.E.A. made and supplied by Hamilton Motors (London), Ltd., 466, Edgware Road, W.2, and the coach was a Leyland Tiger operated by Webster Bros. (Wigan), Ltd., 14, Darlington Street, Wigan. The former company had just completed the conversion, and the demonstration was in the nature of a trial, prior to delivering the outfit to its owner. Only a short run was made, about 20 miles, and no hills of any note were included, but it was sufficient for favourable impressions to be created.

After lighting up. the fire and a short pause for the producer to establish good gas-generating conditions, a start was made from the Hamilton Motors headquarters, and a course wag set to and along Western Avenue. We clicked our stop watch as the driver let in the clutch, and kept it running until, at a point eight miles out, a halt was called, for photography, examination of the apparatus, etc. After the first part of the route, road conditions had been slow, and several halts were necessitated by traffic lights, but, nevertheless, the stop-watch reading for the eight miles was 24 cams. 13 secs., so the average speed was practically 20 m.p.h. We doubt whether this would have been appreciably exceeded on any other fuel. '

It was during this stop and again at the end of the run that the gas made its presence evident to the senses. Its escape is due in fact to a feature of the plant that is claimed to have a markedly good effect upon its performance, namely, that pressure builds up in the system when the throttle is shut. There is a non-return valve in the air intake to the tuyere, so gas cannot flow back through the tuyere when suction ceases, as is usual in other 'producers' which often have a stack pipe on the intake to conduct it away, Accordingly it leaks past the closed air valve at the engine end. We suggest that some means for

dissipating it harmlessly would forestall official criticism. As a result of this pressure in the system the engine is immediately responsive to reopening-s of the throttle; for example, under gear changing conditions, or after slowing

down, or descending a hill. This helps considerably in accelerating the generation of gas at the conclusion of such temporary haltings of the air blast, and improves the effective reactivity of the plant.

Remembering producer-gas trials of a comparable nature in which we have taken part before, of. both passenger and goods vehicles, we are prepared to state in connection with this demonstration, that during the past few years material improvements have been effected. The performance of this LeylandS.E.A. combination inspired the thought that the plant was a practical proposition, and a satisfactory means for any operator to keep his vehicles on the road, and his services contributing their

In the group are Mr. Reader, Coast Lines Ltd. (third from right), and (fifth and sixth from right. respectively) Messrs. Payne and Perry, of the Hamilton Motors concern. The performance was notably satisfactory, the power loss being small.

quota to the national effort, irrespective of whether the ration-issuing authorities regarded them as essential, or otherwise, and untrammelled by bureaucracy, that is, until such time as it may be decided to restrict the use of solid fuel.

A description of the S.E.A. apparatus appeared in our issue dated March 13, but here are some further details with a brief summary of *hat has gone before.

The plant is manufactured in three types—model A, suitable for vehicles having gross weights not exceeding 5 tons; model B, for those weighing all-up not more than 8 tons; and model C, for larger vehicles. Mounted on twowheeled trailer chassis, A costs £146, B £163, and C £170. Built-up on only a sub-frame, models A and B cost, respec tively, 116 13s. and £133 I3s. For sets with neither trailer nor sub-frame, the prices are A 498, B £115, and C £122. These charges do not include fitting.

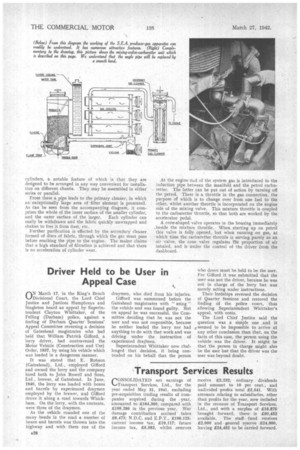

Of the cross-draught dry-blast type, the producer is characterized by its stout construction. Air enters by a water-cooled horizontal tuyere with flame trap and poker door. A tall cylindrical tank dissipates heat and by reason of its height ensures good circulation.

There is a sliding door in the fire-box bottom, by which spent or partly spent fuel can be lowered into the ash box. Another poke hole is set obliquely in the side of the producer to give access to the fire centre and tuyere nozzle. At the top is a cock which can be opened to allow the fire to burn slowly when gas is not being generated and the vehicle is standing.

Connecting the off-take aperture With the cyclone filter is a pipe incorporating a diaphragm joint to prevent any parts from being subjected to stress through temperature changes. From the cyclone the gas flows to three cooling cylinders, a notable feature of which is that they are designed to be arranged in any way convenient for installation on different chassis. They may be assembled in either series or parallel.

From these a pipe leads to the primary cleaner, in which an exceptionally large area of filter element is presented. As can be seen from the accompanying diagram, it comprises the whole of the inner surface of the smaller cylinder, and the outer surface of the larger. Each cylinder can easily be withdrawn and the fabric quickly unwrapped and shaken to free it from dust, etc.

Further purification is effected by the secondary cleaner formed of discs of fabric, through which the gas must pass before reaching the pipe to the engine. The maker claims that a high standard of filtration is achieved and that there is no acceleration of cylinder wear.

At the engine cud of the system gas is introduced to the induction pipe between the manifold and the petrol carburetter, The latter can be put out of action by turning oil the petrol. There is a throttle in the gas connection, the purpose of which is to change over from one fuel to the other, whilst another throttle is incorporated on the engine side of the mixing valve. This mixture throttle is coupled to the carburetter throttle, so that both are worked by the accelerator pedal.

A cone-shaped-valve operates in the housing immediately .beside the mixture throttle. When starting up on petrol this valve is fully opened, but when running on gas, at -which time the carburetter throttle is serving purely as an air valve, the cone valve regulates tre proportion of air inhaled, and is under the control of the driver from the dashboard.