LIGHT and BRIGHT

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

the Guy Warrio _Tight-wheeler

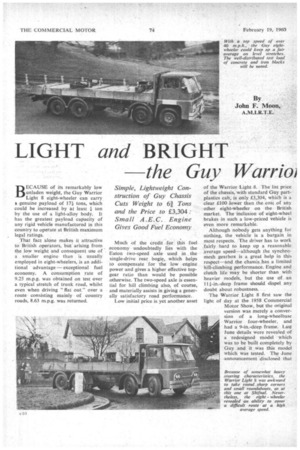

BECAUSE of its remarkably low unladen weight, the Guy Warrior Light 8 eight-wheeler can carry IL genuine payload of 171 tons, which could be increased by at least 71ton by the use of a light-alloy body. It has the greatest payload capacity of any rigid vehicle manufactured in this country to operate at British maximum legal ratings.

That fact alone makes it attractive to British operators, but arising from . the low weight and consequent use of a smaller engine than is usually employed in eight-wheelers, is an additional advantage — exceptional fuel economy. A consumption rate of 9.25 m.p.g. was obtained on test over a typical stretch of trunk road, whilst even when driving "fiat out," over a route consisting mainly of country roads, 8.63 m.p.g. was returned. Much of the credit for this fuel. economy undoubtedly lies with the Eaton two-speed axle used in . the single-drive rear bogie, which helps to compensate for the •low etigine power and gives a higher effective topgear ratio than would be possible otherwise. The two-speed axle is essential for hill climbing also, of course, and materially assists in giving a generally satisfactory road performance..

Low initial price is yet another asset of the Warrior Light 8. The list price of the chassis, with standard Guy partplastics cab, is only £3,304, which is a clear £100 lower than the cost of any other eight-wheeler on the British market. The inclusion of eight-wheel brakes in such a low-priced vehicle is even more remarkable.

Although nobody gets anything for nothing, the vehicle is a bargain in most respects. The driver has to work fairly hard to keep up a reasonable

average speed although the synchromesh gearbox is a great help in this respect—and the chassis ,has a limited hill-climbing performance. Engine and clutch life may be shorter than with heavier models, but the use of an i1-in.-deep frame should dispel any doubt about robustness.

The Warrior Light 8 first saw the light of day at the 1958 Commercial Motor Show, but the original version was merely a conversion of a long-wheelbase Warrior four-wheeler, and had a 9-in.-deep frame. Last June details were revealed of

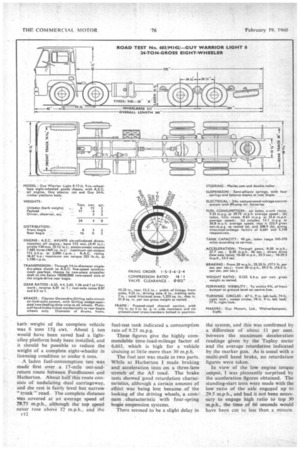

. redesigned model which was to be built completely by Guy and it was this model which was tested. The June -announcement disclosed that a six-wheeled chassis rated for a gross weight of 20 tons was also to be produced. The A.E.C. AVU470 oil engine develops 112 b.h.p. when governed to 2000.

r.p.m., or 125 b.h.p. at 2,200 r.p.m., and the peak torque output of 325 lb.-ft. is produced at .1,100 r.p.m. This torque output is almost 100 MAL lower than that of the smallest engines normally used in eight-wheelers, and I must confess to having been sceptical about the suitability of this unit for a 24-ton-gross chassis.

As the acceleration figures show, however, the Guy is surprisingly lively and on the flat can hold its own against most other heavy vehicles. The A.E.C. five-speed synchromesh gearbox, combined with the doubled-up ratios afforded by the Eaton axle, is a great help in this respect, although there is only one ratio which will give a road speed of more than 30 m.p.h.

Girling two-leading-shoe brakes are fitted to all wheels and are airhydraulically operated through a splitcircuit layout. The newly developed Guy pull-tip hand brake is used, as on the heavy-duty Invincible eightwheelers, and can be supplied with an air servo to take .up the initial slackness in the brake linkage. Without the servo the lever acts as a multi-pull design, but its action was not found to be completely reliable on test.

Michelin " X " 9.00-20-in. tyres are standard and the manufacturers state that their guarantee will be repudiated if larger tyres than this are fitted. This is because the chassis has been designed solely for solo operation at 24 tons

gross, with a rear-bogie loading limit of 16 tons. This was the weight at which I tested it, a Guy driver and myself bringing the weight to 4 cwt. over this figure.

The test vehicle had a standard Guy 24-ft. timber platform body, and the kerb weight of the complete vehicle was 6 tons 15+ cwt. About + ton would have been saved had a lightalloy platform body been installed, and it should be possible to reduce the weight of a complete eight-wheeler in licensing condition to under 6 tons.

A laden fuel-consumption test was madb first over a 17-mile out-andreturn route between Fordhouses and Hatherton. About half this route consists of undulating dual carriageway, and the rest is fairly level but narrow " trunk" road. The complete distance was covered at an average speed of 29.75 m.p.h., although the top speed never rose above 32 m.p.h., and the c12 fuel-test tank indicated a consumption rate of 9.25 m.p.g.

These figures give the highly commendable time-load-mileage factor of 6,661, which is high for a vehicle cruising at little more than 30 m.p.h.

The fuel test was made in two parts. While at Hatherton I made braking and acceleration tests on a three-lane stretch of the AS road. The brake tests showed good retardation characteristics, although a certain amount of effect was being lost because of the locking of the driving wheels, a COITI-' mon characteristic with four-spring bogie suspension systems.

There seemed to be a slight delay in the system, and this was confirmed by a difference of about 11 per cent. between the maximum deceleration readings given by the Tapley meter and the average retardation indicated by the marker gun. As is usual with a multi-pull hand brake, no retardation figures were taken.

In view of the low engine torque output, I was pleasantly surprised by the acceleration figures obtained. The standing-start tests were made with the low ratio of the axle engaged up to 29.5 m.p.h., and had it not been necessary to engage high ratio to top 30 m.p.h., the time of 66 seconds would have been cut to less than a minute. Similarly, because of the axle gearing, direct-drive times could be taken only as far as 29.5 m.p.h., but the time up to this speed from 10 m.p.h. was most satisfactory.

The spread of ratios afforded by the A.E.C.-Eaton gearbox-axle combination is useful. Low axle ratio gives speeds of 5, 10, 19 and 29.5 m.p.h, in second, third, fourth and top gears respectively, whilst the high ratio yields speeds of 8,15, 26 and 41 m.p.h.. in the same gears. Transmission smooth-j ness in direct drive, low axle ratio, was commendable (a Metalastik transmission damper is fitted at the rear universal joint of the rear propeller shaft).

Hilly Test Route

Following the fuel-consumption test under simulated trunk-haulage conditions, I elected to make a further test along less favourable roads between Gailey, on A5, and Bridgnorth, the route being via Shifnal and along 134379 into Bridgnorth. This run was 23 miles long and at times I had to change into bottom gear to ascend some of the hills. On the open road, however, I was able to keep the Warrior cruising at up to 40 m.p.h.

An average speed of 25.6 m.p.h. was maintained over the course, whilst the consumption rate-8.63 m.p.g.—was by no means as heavy as I had feared it would be. Again, a most satisfactory time-load-mileage factor results — 5,348.

Hermitage Hill, Bridgnorth, was used for the hill-performance tests, which were carried out in an ambient temperature of 51° F. This hill is mile long and has an average gradient of 1 in 12 and there are sections of up to 1 in 8. The total climbing time was 8 minutes 10 seconds, during which I brought the vehicle to a standstill twice because I missed changes with the two-speed axle.

I 'had to get down into bottom-low to breast the steepest section, and at this point the road speed fell to 2.5 m.p.h., which would be equivalent to the engine speed at which maximum torque was being developed. Only slight exhaust smoking was observed during the climb and the engine coolant temperature rose from its normal 182° F. by only 4° F.

To check for fade resistance I coasted the eight-wheeler down the hill in neutral and used the foot brake to keep the speed down to about 20 m.p.h. This severe test reduced the maximum braking efficiency by a mere 11 per cent., offering yet further proof of the anti-fade effectiveness of eightwheel brakes on an eight-wheeler.

I then returned to the 1 in 8 section and there I stopped. A fair amount of effort was required on the handbrake lever to restrain the vehicle from rolling back, but once stationary, I just managed to make a bottom-low full-throttle restart. The technique was to apply full throttle, slip the clutch violently while releasing the hand brake, and then to let the clutch in sharply. A slight amount of wheelspin resulted, but the chassis finally moved away.

I would reckon I in 8 is about the steepest slope on which the chassis could safely be restarted, although it should be able to climb short sections steeper than this where it is possible to take a run at the gradient.

The unladen fuel consumption test was made at a gross weight of 6 tons 191 cwt. and the FordhousesHatherton course was used again. The same maximum speed was observed and the resulting overall average speed was little higher than that recorded with the fully laden vehicle. The consumption rate of 15.1 m.p.g. is yet another advantage to be derived from the lightness of the vehicle and indicates that an overall consumption rate of about 12 m.p.g. should be obtained in service when running laden in one direction only.

There is no disguising the fact that the Warrior Light 8 can become a little tiring to drive on hilly, twisting roads. A fair amount of gear changing is almost continually necessary and the steering is heavy. I put this down to the somewhat simple construction of the 4-ton axles used at the front bogie.

Heavy Steering

Steering is particularly heavy at low speeds, and when reversing into a side turning on full lock it is almost impossible to straighten up the wheels until the vehicle moves forward again.

A conventional brake pedal gives good" feel," whether laden or unladen, and the gear-changing action is reasonable in view of the fact that a remote linkage is not employed. Because of the plastics engine cowl, the engine noise penetrating into the cab is passably low at normal speeds.

Details of the cab and its fittings which I did not approve were the diminutive rear-view mirrors (2.1 in. by 6 in.), which are badly placed, and the thoughtless location of the horn push. This is on the off-side door pillar, where it can be inadvertently operated by the driver's right knee. If it were about a foot higher on the same pillar it would be more convenient.

The absence of a main-beam warning light is regrettable, particularly on a vehicle with powerful paired headlights. and I would still like to see additional grab handles to assist access

into the cab and an improved design of door-lock mechanism. These are both points about which I wrote with regard to the Invincible (The Commercial Motor, January 1).

In view of the low price, however, it is perhaps unfair to complain about details, as generally the cab is well thought out and comfortable.

With the exception of access to the fuel filter, maintenance on the Warrior Light 8 reaches a high standard, and operators should find no difficulty in keeping the vehicle up to scratch. The tasks that I carried out were mainly of a fundamental nature, but the ease with which I was able to complete them made a refreshing change.

Water Level Checked

The first job was to check the water level, and the radiator filler cap is easily reached by lowering the " Guy " name plate in the cab front panelling. This check took 15 seconds.

To reach the engine dipstick, the upper cowl section has to be removed completely (it is secured by four spring clips) and this level check occupied 1 minute 20 seconds.

There is a large combined filler and level plug in the left side of the gearbox and I was able to verify the gearbox oil level also in 1 minute 20 seconds. A similar arrangement holds good for the Eaton axle, but because the plug is easier to reach, this level check took only 35 seconds.

Brake adjustment also proved to be easy. Each Girling unit has a single square-headed adjuster, and by jacking up each axle at the centre, so as to lift both wheels off the ground simultaneously, the brakes on each rear axle were adjusted in four minutes and those on each front axle in 2 minutes 10 seconds.

As a final timed check, I dismounted and re-stowed the spare wheel. The wheel has, a winch mounting, and removal entailed detaching two selflocking nuts (which necessitated lying beneath the wheel), releasing two safety catches, and lowering the wheel to the ground. The procedure is reversed for re-stowing. These two tasks took 4 minutes 10 seconds and 3 minutes 10 seconds respectively.

The standard of general accessibility . is commendable and shows that with a little care a commercial vehicle can be easy to work on. For the benefit of those people who might think that I am always able to work under ideal conditions, I might add that immediately before 1 carried out these tasks, the Guy had been standing outside in a snow storm, so that every time I got underneath the vehicle was drenched by melting snow.