The Time Factor

Page 47

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

in the

ROAD versus RAIL STRUGGLE

Some Recent Improvements in Railway Freight Services and a Plain Statement of How Little They Really Mean to' the Average Trader By H. Scott Hall, M.I.A.E.

THERE is a good deal of matter for consideration in a recent communication from one of the railway companies to the effect that it has in three months quickened its freight services by 2,552 minutes. The meaning of that otherwise cryptic statement is better understood by reference to particular examples, such as the Scotland-Birmingham route, on which 420 minutes (seven hours) have been saved, or, better still, by reference to the ScotlandBristol line, on which a saving of 14 bonrs has been effected. This has happened in the past three months.

The most obvious thought is that the stimulant that induced the railway companies to make such prodigious alterations to the time taken on these journeys must have been a powerful one, and, again, that the services must previously have been distinctly dilatory, lacking in consideration for the needs and requirements of traders, for there to be scope for such improvement.

It .does not need much acumen or even more than the briefest contemplation to deduce that the competition from road transport is the impelling force, or to realize that, but for the growing utility of road transport to traders, the railway companies would never have bestirred themselves to the extent indicated by these innovations. Even now they are not so much minded to provide facilities to help trade as to forge weapons wherewith they may wage their battle against road transiprt.

Railways' Lethargic Attitude.

It may, therefore, reasonably be inferred that if ever the railways he successful in their obvious aims, it will not be long before their lethargic attitude towards the needs of the trader will once again be resumed. The moral of that is not far to seek.

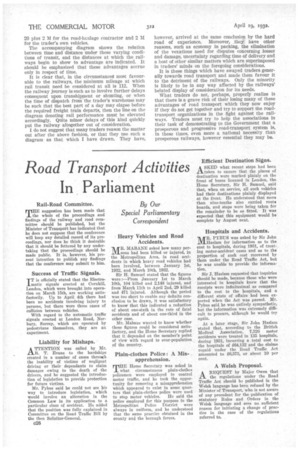

But even these eleventh-hour improvements in freight service are not likely to impress the discriminating trader. The comparative limitations of railway service, whilst somewhat extended by these alterations, are, nevertheless, too well known to him. Ile can, by a simple calculation, determine the preferable means for transport in any case in whichdoubt may arise. Considering time—and it should be borne in mind that only time is affected by this move—there are three factors to be taken into account. First, the period which elapses between the issue of instructions to the company and the placing of the goods on rail (this includes delays in collection as well as time lost in goods yards) ; secondly, the time on rail and, thirdly, that which passes, after the goods have reached the nearest goods station to the consignee and before the actual delivery. It will be convenient to refer to these factors as C, T and D.

When goods are sent by road-transport contractor, factor D is eliminated, only C and T remaining. If the trader has his own fleet of vehicles, C, too, ceases to apply and only T needs be considered.

What the Time Cuts Really Mean.

In the case of rail transit, T varies considerably, according to the route. It is significant to note that all these vaunted cuts in time of transit refer to mainline direct station-to-station journeys, which do not involve the need for transhipment and which do not cater for towns and districts on branch lines, except in so far as the reduction in the time of the main-line journey affects the periods needed between one branch station and another.

For the sake of argument I will take the case most favourable to the railway companies. In those circumstances, T, for these routes, may well be 14 M minutes, where M is the distance in miles ; C is likely to be at least 120 minutes and may be much more, and D at least 60 minutes. Under the most favourable conditions, therefore, the formula for the time needed for a delivery by rail is 180 plus 14 M minutes.

In the case of transit by road-haulage contractor, assuming first that the load is carried in vehicles of the heavier type, T may be 3 M. C will average 20 minutes: it may sometimes be more, but often will be less. The formula is, therefore, 20 plus 3 M. Where the goods are conveyed in the trader's own vehicles the time is 3 M.

If the load be such that a lighter type of vehicle can be used, these formulae become respectively 025 20 plus 2 M for the road-haulage contractor and 2 M for the trader's own vehicles.

The accompanying diagram shows the relation between time and distance under these varying conditions of transit, and the distances at which the railways begin to show to advantage are indicated. It should be emphasized that these advantages accrue only in respect of time.

It is clear that, in the circumstance most favourable to the railways, the minimum mileage at which rail transit need be considered at all is 112. When the railway journey is such as to involve further delays consequent upon transhipment or shunting, or when the time of dispatch from the trader's warehouse may be such that the best part of a day may elapse before the required freight train departs, then the line on the diagram denoting rail performance must be elevated accordingly. Quite minor delays of this kind quickly put the railway altogether out of consideration.

I do not suggest that many traders reason the matter out after the above fashion, or that they use such a diagram• as that which I have drawn. They have, however, arrived at the same conclusion by the hard road of experience. Moreover, they have other reasons, such as economy in packing, the elimination of the vexatious need for disputes concerning losses and damage, uncertainty regarding time of delivery and a host of other similar matters which are superimposed in traders' minds on the foregoing considerations.

It is these things which have swayed traders generally towards road transport and made them favour it to the detriment of the railways. Only the minority Is likely to be in any way affected by the railways' belated display of consideration for its needs.

What traders do not, perhaps, properly realize is that there is a grave risk of their losing many of these advantages of road transport which they now enjoy If they do not get together and try to support bhe roadtransport organizations in the fight against the railways. Traders must try to help the associations in their task of demonstrating to the Government that a prosperous and progressive road-transport system is, in these times, even more a national necessity than prosperous railways, however essential they may be.