h and ;turdy

Page 67

Page 66

Page 68

Page 71

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

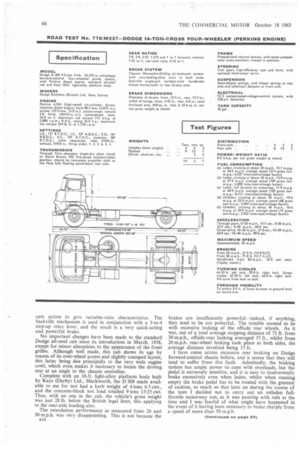

ROAD TEST: Dodge 14-ton-gross, Four-wheeler (Perkins engine) ROBUST, straightforward construction has for long been one of the prime attractions of British Dodge goods chassis, and this has ensured their popularity in a great number of overseas countries in addition to the home market. One of this Kew company's latest forwardcontrol designs is the D 309 four-wheeler, which was announced last April and which has a nominal payload rating of 9-5 tons, the actual gross solo rating being 13.7 tons whilst the recommended train-weight rating is 20 tons.

It is obvious that this model will be used in this country at the legal maximum of 14 tons, and it is well able to stand this, as the standard front and rear axles are rated for 5and 9.5-ton loadings respectively, whilst the chassis frame has 0.3125-in.-thick side members, with a maximum depth of 10 in., and 3-in. flanges.

The standard engine in the D 309 is the high-rated version of the Perkins 6.354 direct-injection diesel, and a recent road test of a model with this power unit showed that, although by no means over-engined, the fuel economy was good and the general road performance entirely satisfactory, bearing in mind that the test vehicle had the highratio single-speed axle, and was thus geared more for longdistance running than for lively short-haul work. Unfortunately, the braking performance was not up to the standard of the rest of the chassis, and the recorded stopping distance was 71 ft. from 30 m.p.h.

Details of the latest Dodge forward-control models were given in our April 5 issue, this report indicating that the 9-5-tortner replaced the original 9-ton design, whilst at the same time costing some £300 less. There are several versions of the D 309, including a 9-ft. 8-in.-wheelbase tipper chassis and two normal load-carriers, with wheelbases of 13 ft. 7 in. and (as tested) 14 ft. 10-375 in. The short-wheelbase model has a gross solo rating of 13 tons unless an Eaton 18802 Mk. I two-speed axle is specified.

The old 9-tonner had the A.E.C. AV 410 118-b.h.p. (net) B" diesel as standard, and this is still available in the D 309 as an option to the Perkins engine, the extra price involved being £232 because a 14-in. clutch, David Brown 552 gearbox. 24 V electrical system and air-hydraulic brakes are standard with this A E.C. engine, these items combining to increase the chassis weight by 413 lb. When this engine is fitted the David Brown box with overdrive-top can be supplied, but in this case a two-speed axle cannot be used.

David Brown Option With the standard Perkins engine an E.N.V.-Dodge fivespeed constant-mesh gearbox is normally fitted, but for £48 extra a 14-in, clutch and the direct-top David Brown box can be supplied, this box having similar ratios to the E.N.V. type, but greater strength margins.

Irrespective of the engine or gearbox choice, the standard driving axle is a Moss 900-series spiral-bevel assembly. available with ratios of 6-16 or 6-66 to I.

Except when the overdrive box is fitted, there are two Eaton two-speed axle alternatives--the 16802 Mk. V, with a capacity of 9-4 tons, and the 18802 Mk. I, with a capacity of 9-8 tons. These axles have slightly lower ratios when the 6.354 is installed than when used with the A.E.C. engine, and the price extras involved are £105 and £155 respectively.

Obviously considerable thought has gone into the design of the suspension of this chassis, for my tests showed that it rides, extremely well under all conditions of load and road. Three-inch-wide springs are used at front and rear, the single-rate front springs being 50-in, long and having 13 leaves, whilst the dual-rate rear springs which have integral helper leaves—are 54-in, long and have a total of 20 leaves. The test vehicle had the optional telescopic dampers at the front axle, which help to make the ride exceptionally smooth, whilst the rear-spring assemblies were the optional extra-duty type, which cost £4 10s. more than the standard springs and contain 22 leaves. Dampers are available for the rear suspension also, though my own view is that they are hardly likely to be necessary under normal conditions.

Mr-hydraulic Brakes

As with most current Dodge heavy chassis, the D 309 has Girling brakes, with air-hydraulic actuation in the case of the test chassis, although this equipment is classed as an optional extra (at £34) to the standard vacuum-hydraulic system, the servo for which is of the Hydrovac type. The handbrake lever is a Sackville single-pull assembly, with cam action to give variable-ratio characteristics. The Sackville mechanism is used in conjunction with a 5-to-4 step-up relay lever, and the result is a very quick-acting and powerful brake.

No important changes have been made to the standard Dodge all-steel cab since its introduction in March, 1958, except for minor alterations to the appearance of the front grilles. Although well made, this cab shows its age by reason of its over-wheel access and slightly cramped layout, this latter being due principally to the very wide engine cowl, which even makes it necessary to locate the driving seat at an angle to the chassis centreline.

Complete with an 18-ft. light-alloy platform body built by Kays (Derby) Ltd., Mackworth, the D 309 made available to me for test had a kerb weight of 4 tons 6-5 cwt., and the concrete-block test load totalled 9 tons 13.25 cwt. Thus, with no one in the cab, the vehicle's gross weight was just 28 lb. below the British legal limit, this applying to the rear-axle loading also.

The retardation performance as measured from 20 and 30 m.p.h. was very disappointing. This is not because the B34

brakes are insufficiently powerful—indeed, if anything, they tend to be too powerful. The trouble seemed to lie with excessive locking of the offside rear wheels. As it was, out of a total average stopping distance of 71 ft. from 30 m.p.h., offside-rear locking averaged 57 ft., whilst from 20 m.p.h. rear-wheel locking took place at both sides, the average distance involved being 17 ft.

I have come across excessive rear braking on Dodge forward-control chassis before, and it seems that they still tend to suffer from this fault. Admittedly, the braking system has ample power to cope with overloads, but the pedal is extremely sensitive, and it is easy to inadvertently brake excessively even when laden, whilst when running empty the brake pedal has to be treated with the greatest of caution, so much so that later on during the course of the tests I decided not to carry out an unladen fullthrottle motorway run, as it was pouring with rain at the time and I was fearful of what might have happened in the event of it having been necessary to brake sharply from a speed of more than 50 m.p.h. It seems a shame to have to criticize an otherwise very satisfactory vehicle on the grounds of faulty braking-system design, but fortunately the problem is by no means insurmountable.

At least the handbrake performance is above average, the Tapley meter indicating a maximum retardation of 35 per cent from 20 m.p.h,—without wheel locking. This Sackville brake is obviously a very satisfactory answer to poor handbrake performance, and is undoubtedly to be preferred to a multi-pull brake on the grounds of its quick action.

The acceleration tests, whilst they revealed a fairly satisfactory through-the-gears performance, suggested that the test chassis tended to be over-geared and the alternative 'single-speed-axle ratio of 6.66 to 1 would have produced a more lively performance, particularly in top gear. However, the 6-16-to-1 axle is probably the best for longdistance haulage work, whilst operators requiring a combination of good gradient performance, lively acceleration and high top speed could always settle for one of the Eaton axles. Slight roughness at the gearbox was revealed when making the direct-drive tests, which further supports my view that the vehicle was over-geared, whilst the directdrive figures themselves indicate the sluggish performance in this ratio.

Good Fuel Consumption

All the fuel-consumption results obtained and detailed in the accompanying data panel show good economy for a 14-ton vehicle and, furthermore, suggest that this highrated version of the Perkins 6.354 is no less economical than the original standard version still used by most manufacturers and which produces 7.6 per cent less b.h.p., whilst the maximum torque output is 91b. ft. less.

Hill-climbing performance was checked on Bison Hill, a 0.75-mile-long gradient with an average severity of I in 10-5. A climb was made in an ambient temperature of .17"C (62.5°E), and the 3-min. 50-sec. ascent caused a rise in engine-coolant temperature of 12°C (21-6°F), the final water temperature being 83°C (181-4°F). Unfortunately, one of the stop watches I was using gave up the ghost during the ascent, so the total climbing time was not recorded. However, the other watch used to check time in the lowest gear showed that bottom had been engaged for 2 min. 12 sec. whilst the lowest recorded speed was 7 m.p.h. No smoke was noticed at the exhaust during this climb.

As usual, fade resistance was checked by coasting down Bison in neutral at 20 m.p.h., and this descent lasted 2 min. 33 sec, at the end of which time a full-pressure stop from 20 m.p.h. showed that the maximum footbrake efficiency had been reduced by 0-18g, showing quite good resistance to fade. This stop was made without any of the wheels locking, but both the brakes on the offside were smoking profusely by the time the test was made.

I then returned the Dodge up the hill and stopped it on the 1-in-6-5 section, where the handbrake held it easily, following which a smooth bottom-gear restart was carried out, albeit with the use of full throttle. After this the vehicle was turned round and the restart tests repeated facing down the hill. Again the handbrake was amply powerful enough to hold the vehicle without excessive effort on the part of the driver, whilst full throttle was needed to get away back up the hill.

As already remarked, the suspension of this Dodge chassis reaches a very high standard indeed in both the laden and unladen conditions, and this helps to make life more pleasant for the driver in addition to reducing the risk of damage to the load, the bodywork and the chassis. Road bumps were not felt at the steering, although the vehicle tested had the optional Hydrosteer hydraulic steering servo, which would tend to absorb shocks in any case.

Pleasant Steering Although it is questionable as to whether steering power assistance should really be necessary on a vehicle with only a 5-ton front-axle loading, the steering of the Dodge was certainly pleasant, apart from the rather meagre castor action, which made it necessary to feed the wheel back after taking a corner quickly. The servo effect was by no means too pronounced, so there was no fear of instability, over-correction or wander, even at speeds in excess of 50 m.p.h., whilst when unladen also the steering was completely satisfactory, except that the castor effect was even less.

The vehicle tested had a quilt over the engine cowl, so that the noise in the cab was quite reasonable except when pulling hard at close to governed speed. Then booming and resonance were audible. With the quilt raised, the noise level was somewhat excessive. The engine pulled well but, as I have already said, was having to work against too high an axle ratio. If a six-speed gearbox with overdrive top were available for this sire of engine this could have been used in conjunction with the 6.66-to-I axle and so give a better overall performance, but unfortunately a suitable box does not appear to be offered in this country.

The David Brown box fitted in the test vehicle gives a fairly satisfactory spread of ratios, but because the gearchange lever is located well behind the engine cowl some of the gear changes are a bit awkward, particularly from two to three and from four to five. Gear changing is not helped by the rather heavy clutch-release action either.

Apart from various outdated features and the lack of interior space, the Dodge cab isn't too bad for a massproduction assembly. and the finish is quite good. Visibility to the front and sides is adequate, but the position is not so good to the rear, partly because the mirrors—although large— are mounted low down on rather short arms, so do not give the full range of vision that they would if they were better mounted.

The standard list price of the Dodge D 309 chassis-cab is £1,881. Extras fitted to the test vehicle, in addition to those already referred to and priced, included the steering servo at £40, the front dampers at £9 10s, the single cab heater at £17 10s., dual Windtone horns at £3 5s., front towing eyes at £2 and flashing direction indicators at £8. Thus the total chassis-cab price as tested is £2,047 15s., whilst the Kays body costs £274.