MUNICIPAL AERODROMES

Page 111

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

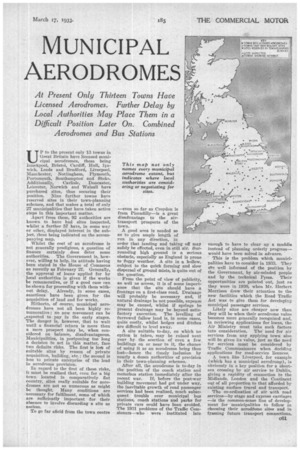

P to the present only 13 towns in Great Britain have licensed municipal aerodromes, these being lsiackpool, Bristol, Cardiff, Hull, Ipswich, Leeds and Bradford, Liverpool, Manchester, Nottingham, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Southamptonand Stoke. Additionally, Carlisle; Doncaster, Leicester, Norwich and Walsall have purchased sites, thus securing their position. Nine further towns have reserved sites in their town-planning schemes, and that makes a total of only 27 municipalities that have taken active steps in this important matter.

Apart from these, 92 authorities are known to have had sites inspected, whilst a further 57 have, in some way or other, displayed interest in the subject, these being indicated on the.accompanying map.

Whilst the cost of an aerodrome is not generally prodigious, a question of finance certainly does deter some authorities. The Government is, however, willing to help, its attitude having been stated in the House of Commons as recently as February 27. Generally, the approval of loans applied for by local authorities is given if the works be remunerative, or if a good case can be shown for proceeding with them with out delay. Already, in some eases, sanctions have been given for the acquisition of land and for works.

Hitherto, of course, municipal aerodromes have not all been highly remunerative; no new movement can be „expected to pay in the early stages. The danger is, however, that to wait until a financial return is more than a mere prospect may *be, when considered on balance, disadvantageous. Municipalities, in postponing too long a decision to act in this matter, face two definite risks. The first is losi3 of suitable sites by reason of private acquisition, building, etc.; the second is loss to private enterprise of the lead in aerodrome provision.

In regard to the first of these risks, It Must he realized that, even for a big town located in comparatively flat country, sites really suitable for aerodromes are not so numerous as might be thought. Many conditions are necessary for fulfilment, some of which are sufficiently important for their absence to involve discarding a site as useless.

To go far afield from the town centre —even so far as Croydon is from Piccadilly—is a great disadvantage to the airtransport prospects of the town.

A good area is needed so as to give ample length of run in any direction, in order that landing and taking off may safely be effected, even in still air. kSurrounding high ground is a serious obstacle, especially as England is prone to foggy weather. A site in a hollow, subject to the quick forming and slow dispersal of ground mists, is quite out of the question.

From the point of view of publicity, as well as access, it is of some importance that the site should have a frontage on a first-class road. Drainage will probably be necessary and, if natural drainage be not possible, expense may be caused, whilst if springs be present drainage may be beyond satisfactory execution. The levelling of furrowed fallow land is, in some cases, quite costly, whilst hedges and ditches are difficult to level away.

A site suitable to-day, on which no option is taken, may be ruined next year by the erection of even a few buildings on or near to it, the chance of using it as an aerodrome being thus lost—hence the timely inclusion by nearly a dozen authorities of provision in their town-planning schemes.

After all, the aerodrome is to-day in the position of the coach station and motorbus station immediately after the recent war. If, before the post-war building movement had got under way, the inevitable growth of road passenger services had been realized, much subsequent trouble over municipal bus stations, coach stations and parks for private cars could have been avoided. The 1931 problems of the Traffic Comsioners—who were instituted late enough to have to clear up a muddle instead of planning orderly progress— would have been solved in advance.

This is the problem which municipalities have to consider in 1933. They ate well informed of the position by the Government, by air-minded people and by the technical Press. Their opportunities are pointed out, just as they were in 1930, when Mr. Herbert Morrison drew their attention to the new facilities which the Road Traffic, Act was to give them for developing municipal passenger services.

Likely sites are cheaper now than they will be when their aerodrome value becomes more generally recognized and, in reviewing applications for loans, the Air Ministry must take such factors into consideration. Theneed for air services from any applying town also will be given its value, just as the need for services must be considered by Traffic Commissioners when deciding applications for road-service licences.

A town like Liverpool, for example (which has a municipal aerodrome), is obviously in a key position for a shortsea crossing by air service to Dublin, giving a rapidity of connection to the Midlands. London and the Continent oat of all proportion to that afforded by existing surface travel and transport.

The co-ordination of air with road services—by stuge and express carriages —is the common-sense line of development for municipalities to follow in choosing their aerodfome sites and in framing future transport connections.