PHOTOGRAPHY by STEVE BROOKS

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

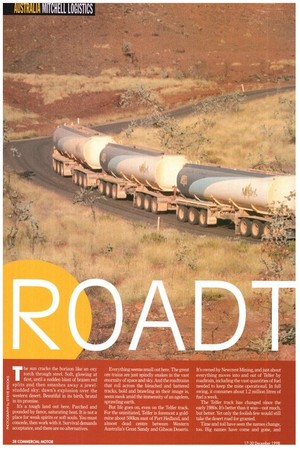

The sun cracks the horizon like an oxy torch through steel. Soft, glowing at first, until a sudden blast of brazen red splits and then smashes away a jewelstudded sky: dawn's explosion over the western desert. Beautiful in its birth, brutal in its promise.

It's a tough land out here. Parched and pounded by fierce, saturating heat. It is not a place for weak spirits or soft souls. You must concede, then work with it. Survival demands acceptance, and there are no alternatives. Everything seems small out here. The great ore trains are just spindly snakes in the vast enormity of space and sky. And the roadtrains that roll across the bleached and battered tracks, bold and brawling as their image is, seem meek amid the immensity of an ageless, sprawling earth.

But life goes on, even on the Telfer track. For the uninitiated, Telfer is foremost a gold. mine about 500km east of Port Hedland, and almost dead centre between Western Australia's Great Sandy and Gibson Deserts. It's owned by Newcrait Mining, and just about everything moves into and out of Telfer by roadtrain, including the vast quantities of fuel needed to keep the mine operational. In full swing, it consumes about 1.2 million litres of fuel a week.

The Telfer track has changed since the early 1980s. It's better than it was—not much, but better. Yet only the foolish few would still take the desert road for granted_ Time and toil have seen the names change, too. Big names have come and gone, and there's a new breed weighing their wits against the heatwaves and weights. One of these is a family by the name of Mitchell.

The Mitchell Logistics name has grown to considerable prominence in the Western Australia fuel haulage business as a distributor of BP fuel products, and is now likely to grow further since the company's recent win of a contract to haul BP fuel throughout the Perth metropolitan area.

But the home base is Geraldton, about 420km north of Perth, where company founder and principal Pip Mitchell directs a fleet well known for pushing the productivity envelope. The company has been a BP contractor since 1986, hauling deep into Western Australia's eastern backblocks. About 12 years ago it took the plunge into aluminium tanker barrels and air suspensions when tradition still said only steel tankers and suspensions could survive the rigours of remote off-road work. The plunge has paid off, big time.

Likewise the initial move to ti-drive. Today • the company is unquestionably the most prolific user of tri-drive prime movers in Western Australia, with nine triple diff units, including

three new 10x6 Kenworth K100Gs two of them for the Teller run—in a fleet of 40 trucks and 90 trailers. In fact, it seems the majority of roadtrain equipment in the Mitchell fleet these days sits on three-axle groups; tii-axle dollies, tri-axle tankers and, of course, tridrive prime movers.

The boss

Heading the new division is 25-year-old Craig Mitchell, who explains that the Telfer job was won by, and falls under the aegis of, the logistics arm. The old hands might think the Telfer task a tough call for someone so young, but Mitchell dismisses any suggestion of inexperience. "I've been brought up in the transport business. It's what I know, and sure, I can still learn, but so can everyone," he says with simple logic.

The Telfer work was not the initial reason for Mitchell's move north into Port Hedland. When Jim Firns, long-time Hedland distributor for BP, decided to sell, Mitchell was quick to buy what was a secure and established operation. That was in early 1997. Three months later the Telfer job came up for tender, and with the former Firns operation as a solid foundation Mitchell threw its hat into a congested ring.

"We were a late tenderer against some major players chasing the work," he says, "but we were confident because we were prepared to run bigger equipment than anyone else. And we went in with a highly competitive price. We knew we could do the job better and with fewer trucks, but we had to win it first."

Still, Mitchell concedes that doing the job "bigger and better than anyone else" meant putting faith and experience into practice like never before. There was no doubt in Mitchell that the Telfer work would be the toughest the company had ever undertaken, and although others would perhaps see the decision to run Tieman aluminium tanker barrels riding on BPW axles and air suspensions and running on Alcoa alloy wheels as a risky gamble on the notorious Telfer road, the payload benefits were far too great to ignore. To the Mitchells, though, experience suggested the risk wasn't nearly as great as others thought. As for the decision to run the same running gear under all the dollies and tankers ordered for the Telfer work, fleet standardisation was a high priority.

Similarly, total reliance on triode groups running on concessional permits which allowed 23.5 tonnes loading on each group was deemed essential to maximise productivity. The same reliance demanded a unique truck—tri-drive, of course and Mitchell is quick to acknowledge Kenworth's experience and expertise in building dedicated trucks for a dedicated purpose. It's one which has already served Mitchell Logistics well for many years.

So the end result was three twin-steer, tridrive K100Gs ordered through Western Australia Kenworth dealership CJD Equipment, and surprisingly, the first 10x6 units built at Kenworth's Bayswater (Vic) factory. Drivelines are identical to Cummins N14E 525hp engines feeding through a Spicer Solo clutch into Eaton's RTLO-18718B 18speed double overdrive transmission, and Mentor's (nee Rockwell's) RZ78-388 tridem with a final drive ratio of 5.52:1 riding on the latest generation of Hendrickson's homegrown WD3-600 airbag suspension.

The decision to run K100Gs rather than the T950 conventionals common to the modern Mitchell roadtrain fleet was based purely on productivity. With an overall length within the 53.5m limit, and the weight-carrying benefit of a twin-steer front end, the cab-ovens allow maximum utilisation of space and payload for a job which demands peak carrying capacity on every trip.

Two of the trucks are configured as prime movers, hauling a B-double up front with two tankers behind. Only one of these two, however, hauls to Telfer. The other works out of home base at Geraldton.

On the surface, the prime mover configuration has a relatively modest carrying capacity of 119,000 litres of fuel, but, as Mitchell Logistics operations manager Paul Hitchcock points out, versatility comes into play: "The two lead trailers behind this truck are fitted with demountable tubs for carrying copper concentrate back from Telfer." About 46 tonnes of concentrate are hauled back to Port Hedland on each trip.

But the big banger of the batch is a 10x6 body truck hauling three tankers. All-up carrying capacity is in excess of 140,000 litres. Allowable gross weight is up to 175.5 tonnes.

Weights of this magnitude are hard work on any road. On the Telfer track they're brutal in the extreme. Mitchell knows it, but his faith in the quality of the equipment and people around him is undaunted. What's more, it seems well and truly justified.

It's a 1,000km round trip from Hedland to Telfer. All things going well, and including unloading time, it takes the fuel drivers between 22 and 25 hours to cover the run.

'No drivers are allocated to each of the two tri-drive Kenworth Aerodynes, working on a trip on/trip off basis. In a full week the two trucks will deliver up to 1.6 million litres of fuel to the Teller mine. However, if there's an unforeseen problem with a truck or a sudden increase in demand, Mitchell Logistics has plenty of reserve transport, with seven triple tanker combinations and 12 drivers now working from its Port Hedland yard.

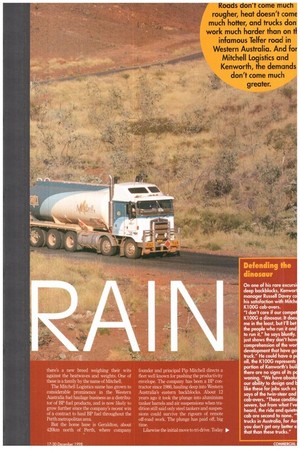

The first few hours of the trip to Telfer are the easiest, hauling on good bitumen. After that it gets down to serious business, with average speeds rarely above 501cm/h and climbs, particularly at these weights, which can consume horsepower and torque with savage and surprising audacity. Summer temperatures of 50°C are not unusual, while road conditions range from reasonable to rotten, depending on where the road grader's working at the time. Creek beds as dry as a dead dingo can turn into impassable torrents when a cyclone hovers off the Hedland coast.

Kenworth praise

Accolades aren t given casually, but Mitchell driver Mark Cavey feels nothing but delight for the introduction of the Kenworth cabovers late last year. Mark shares the 10x6 body truck with John Dearsley, and says the ride quality and general on-road manners of the cab-over are "just excellent, and better than anything I've driven on this road before, including a few European makes".

Complaints are few. "The gearlever rubs your left leg a bit, and the cable gearshift's too stiff. Other than those, I've nothing but praise for the truck," he says candidly. "I know it's early days, but everything's right so fat" On performance: "I think any engine would work hard at these weights on this road, but the Cummins is strong enough for the job. It does it well."

So about four hours into the outward leg came the question, "Would ya like to have a steer?" We didn't have to be asked twice.

The last Kenworth CM had driven on this road, eight years ago, was an eight-wheeler K100E body truck pulling three trailers. Gross

weight was about 120 tonnes. The mad was wickedly rough, but with its set-back front axles and what turned out to be poor suspension geometry, the cab-over was a shocker even by Telfer standards. And the steering was almost as bad as the ride.

Yet other than the badge on the front and the view through the screen, Mitchell's KlOOG bore absolutely no resemblance. In fact, it's an absolute gem. Exceptional ride quality positive steering, ample headroom and a great dash layout. Sure, the road's marginally better, but this truck is light years ahead of Kenworth's former cab-over family.

Still, Cavey was right. The gearlever rubs your left leg, and in this particular truck the cable gearshift was far too tight and vague.

In reality, however, the Cummins 525 certainly wasn't shy about demonstrating its reserves of grit and determination. On the sharp jump-ups which arrive with sudden severity on the Telfer track, the willingness and response of the Cummins were both potent and surprising. And there's another re the 525hp and 1850Ibft although it's one thing 600hp and more than 200 torque, it's something con different to feed it throug line components still evol the point of accepting ma sive outputs in such bruta tions and under such en weights.

So is the 600hp and engine worth the durabil particularly when current nations such as a 525hp Ct Eaton 18-speed transmiss. Mentor heavy-duty rear a already delivering adequa a question with no quick according to Mentor' Grumont.

"In torque and weigl drivetrain envelope is c being pushed to new lin says. "hi applications E Mitchell's Telfer work c components are at theii limit, and it needs to be e...) that each application a weights and operating co: must be assessed and a: individually."

Mitchell is quick to "That's why we believe t are a good way to go," he e "Not just for the extra weight-carryin ity, but because you're spreading thi through three drive axles rather than adds, At these weights, there's als benefit with traction on the jump-ups.

It's early days, though. When we behind the wheel of Cavey's truck th only 30,0001on on the clock, yet acco Mitchell Logistics service manaf Templeton, there's no reason for pes

"We've had no real shake-down with the trucks, probably because tldesigned from the ground up for tlwork. At this stage I don't think we any happier with the way they're says candidly.

"Trucks and trailers go over the minor service after every trip, and th get a major service every third trip Telfer run, you soon find out if the thing wrong." Indeed you do.

by Steve Brooks

Defending the dinosaur

On one of his rare excursi deep backblocks, Kenwor manager Russell Davey co his satisfaction with Mitch K1 00G cab-overs.

"I don't care if our compe KlOOG a dinosaur. It does me in the least, but I'll bet the people who run it and to run it," he says bluntly. just shows they don't hay comprehension of the wo development that have go truck." He could have a p all, the K100G represents portion of Kenworth's buil there are no signs of its waning. "We have abso u our ability to design and like these for jobs such as says of the twin-steer and cab-overs. "These conditi severe, but from what I'v heard, the ride and quietn cab are second to none." trucks in Australia, for Au you don't get any better e that than these trucks."

Tri as you might

According to CJD Equipment's truck division manager John Corderoy, a trend to hi-drive prime movers for heavy-duty roadtrain jobs first emerged in Western Australia four years ago. Today there are around 20 Kenworths with triple diff assemblies in Western Australia, primarily in fuel and tipper applications. To a lesser extent, Mocks, Western Stars and Internationals are also found in tri-drive configurations.

On Kenworth's figures, the price premium for a tri-drive prime mover is about 10% over and above a traditional tandem drive unit. "The enquiry for tri-drives is fairly static at the moment," Corderoy explains, "but there's certainly the potential for it to grow. In Western Australia much depends on how the mining industry's going. "Tr-drives are a very application specific thing," he adds. "Unless a particular job has a big problem with traction, a tri-drive is of little or no benefit without a concessional permit to carry extra weight on the tri group. Tr-drives are certainly right for some heavy-duly roadtrain jobs, but not all."