The Dean of Drivers goes 'out of this world'

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

SWEDEN has earned itself a reputation for leading the world in vehicle safety standards. How. appropriate then that at a time when vehicle safety is very much in the news this should be the country visited by Harold Dean, CM's Lorry Driver of the Year 1980, for his Michelin Study. Tour Award. And what a tour!

At the end of the five day visit Harold described it as "out of this world," and the entire party, comprising Harold, Len Bassett — director of the Bassett Group of Companies (Harold's employer) — Chris Rogers from Michelin, and myself agreed that the experience gained on the tour and the warmth of Swedish hospitality had made it a week none of us would forget.

First stop was Gothenburg (G6teborg if you prefer the Swedish) where Volvo has its headquarters and on the outskirts of which town is the famous Torslanda Volvo car plant. While commercial vehicles were of course the main interest for Harold and Len we couldn't visit Gothenburg without at least spending a short while at a car plant renowned for advanced assembly processes and excellent labour relations record.

It soon became clear why the Torslanda workforce should have so few grievances — they have superb working conditions and a job rotation system to relieve the monotony of assembly line working. Noise levels inside the plant were remarkably low even in the press shop which, our guide told us, has a wooden floor, purely to help absorb the noise. Computers are used extensively at Torslanda which claims to have the most automated car body welding line in the world. Robots tackle 97 per cent of the welding jobs on the Volvo car assembly line, and that is an even higher degree of automation than Fiat's Strada line, claims Volvo.

It was a slightly unnerving experience to see the bodies proceeding through several stages, being spot-welded here and there by mechanical arms, seemingly with minds of their own, and not a human being in sight. But then even the most skilled human welders could not match the expertise of this mechanical workforce which can weld 50 car bodies an hour within fine tolerances and make 700 spot-welds every 72 seconds, And of course they don't get tired, bored or careless.

At lunch our host at the Volvo Truck Plant was managing director of the Volvo Truck Corporation Sten Langenius. I think Harold was a little surprised that conversation with Mr Leangenius was so easy. Like so many Swedes he speaks perfect English, but he is also able to relate to the everyday problems drivers face.

Sten Langenius holds an hgv class 1 driver's licence and makes a point of regularly driving the vehicles his company manufactures. Earlier this year, for example, he spent two days driving Volvo lorries in England and Scotland and more recently he and Volvo Trucks product planning manager Leif Strand went incognito to the Soviet Union in an F10.

"The first-hand experience we gain from trips such as these is invaluable," Mr Langenius told us, "We learn what features drivers of long-distance vehicles would really appreciate." Now that it is fairly common for tractive units to have cab suspension, suspension seats, low interior noise levels and a generally high standard of driver comfort, Len Bassett wondered what would be the next major change in can design.

Leif Strand was not about to reveal any Volvo secret plans, but he did say that more manufacturers could be fitting air conditioning in future as Volvo has done on its F10 and F12 ranges. Apart from that he expected any changes in vehicle design to be "evolutionary rather than revolutionary."

The most recent addition to the Volvo range is the F12 Globetrotter which is available in the UK fitted with the "normal" F12 TD120C engine rated at 243kW (326bhp), (CM, 40-tonr test, October 25) but in Scanc navia the Globetrotter is fitte with an intercooled version this engine rated at 26510 (360bhp). This was to be oi means of transport betweE Goteborg and SkOvde whei Volvo has a foundry and plai producing petrol and diesel ei gines.

It gave our Driver of the Ye, an eagerly awaited opportuni to drive on Swedish roads at timaximum weight allowed, E tonnes (51.2 tons), and at maximum length of 24m (78.7f1 As a regular driver of an arti ulated vehicle, Harold Dean wi• pleasantly surprised at the rel. tive lack of "cut in" of drawbar combination and eve with an overall length some 91 (301t) longer than he was used) he had little difficulty in adaptir to the vehicle. The fact that v% were at a gross weight of f. tonnes went virtually unnoticei for the inter-cooled 12-liti Volvo engine always had powi to spare in spite of an o casionally slipping clutch. Thei

is a 70km/h (44mph) maximum speed limit for heavy vehicles on Swedish roads but the normal motorway pace is about 80km/h (50mph).

As we headed North-east towards Skovde on the E3 Harold commented on the lack of traffic, but our accompanying Volvo driver told us it was about normal density for a midweek afternoon. Remember, Sweden covers a greater area than the United Kingdom but its total population of eight million is less than that of Greater London. The most common road hazard, we were told are straying elk that often cross unfenced roads — a far cry from Britain's crowded highways.

Harold was impressed by the courtesy shown by Swedish drivers, especially hgv drivers. The E3 is basically a two-lane road with no central reservation, but between each lane and the edge of the road on each side is a sort of "hard shoulder" — a lane of about half the normal width which is not normally used.

But whenever a lorry driver sees that someone wants to overtake he will move over into the narrow nearside lane to make room, but only if he can see far enough ahead to be sure it is safe. In other words if a potential overtaker sees a lorry remain in the lane in front of him he knows that it is unsafe to pass at that point.

After a little initial uncertainty, Harold's verdict on Volvo's new 12-speed gearbox was also favourable. Having driven an F7 with Ron Cater at CM'S Fleet Management Conference (CM, October 18) Harold was already a convert to the principle ol synchromesh gearboxes. While of course it is fully synchromesh, Volvo's new SR70 gearbox for the intercooled Globetrotter is not an eight-speed rangechange unit like those used in the F7, F10, F12.

It is basically a three-speec gearbox with a high and low range and a splitter on each gear. A high and low crawler gear gives a total of 14 forwarc ratios, and the shift pattern is ir the conventional H-form of z four-speed gearbox but without the fourth gear.

Another departure from nor. mal Volvo practice is in the loca. tion of the splitter switch whictis fitted on the gearlever and no remotely mounted. For Harold as for any driver new to thE vehicle, at first it was difficult tc remember which was the spline' and which was the range. change switch but even if they'rE mistaken the gearbox's inhibitoi prevents expensive damage as i. prohibits low range from beinc engaged at too high a speed.

We had not been at thE Skovde plant very long beforE the topic of conversatior changed from gearboxes to en gines — hardly surprising sincE this is the plant where all Volvc 7-, 10and 12-litre diesel engine: are made as well as some Volvc car petrol engines. Our guidE through the plant was qualit) control manager for diesel en gines Rune Persson who told u: that the output from the plan was around 50,000 units a year About 13,000 ten-litre engine: will be produced this year, morE than any other single diesel en gine type.

In contrast to the Torsland: car plant the work at Skewde ir much more labour-intensive. En gine-building remains a high!) skilled task, but wherever pos sible Volvo has relieved thE workforce of tedious tasks. Fo example, painting complete( engines is a very necessary job i the units are to reach the cus tomer in top condition, but no body likes the job.

Rune showed us Volvo's solu tion to the problem — an auto matic spray booth into vvhict

continued overlea L:ompleted engines run on their ...-radles. Before each engine goes into the booth, it is scanned D y several photoelectric cells on 3 gantry. These cells "see" what :ype of engine it is by recoglising its profile, the position of :he turbocharger and so on, and :hen program the booth accordngly.

The foundry at Skovde is lascinating. Apart from the /arious engine blocks, we saw nany other Volvo components )eing cast for lorries and cars and even some brake drums for JoIva's arch-rivals Saab. Only 20 )er cent of the raw material used n the foundry is "new" iron, the 'est is recycled scrap from car )odies and the like. When the nolten metal leaves the hoppers

n the foundry it is at a temperaure of about 1,400°C and even he ceramic linings can only ;tend this treatment for a limited )eriod, they have to be replaced ,ach week.

Another intriguing thing about he foundry is that sand from it is )xported to, of all places, Saudi krabia. That country has more han enough sand of its own, but lone of it is of a high enough ivality.

Harold's tongue-in-cheek reiuest to take Globetrotter back o England for an extended trial vas politely refused by Volvo. \fter all it would be vastly )verlength and overweight, so ve turned from road to rail as a neans of transport between ikovde and Stockholm, the lext city on our itinerary and ,ome 280km (174 miles) to the Jorth-east.

At about this stage of the tudy tour I began to understand he tomato-ketchup bottle analigy of Swedish friendliness: you hake it, but at first nothing omes out. But then the top omes off and the ketchup flows orth.

By now Harold was known as )ixie to our companions from Aichelin Sweden Richard Haland Lennart Sandstedt, nd Irish jokes from the British ontingent were being counared by Norwegian jokes from le Swedes.

On a more serious note, -lough, much of the time on the -ain journey was taken up by a vely discussion about the pros nd cons of British and Swedish ghting regulations. In Sweden, riving or "recognition" lights lust be used all the time and tatistics suggest that this regu)tion has helped to reduce the umber of road accidents.

Yet high-intensity rear lights re not currently allowed in weden. Dixie agreed with me -lat if they continue to be missed in the UK, dazzling more

drivers than they warn, then perhaps it would be better if they were no longer permitted.

At Stockholm railway station we were met by Rolf Laag and Hans Str6mberg from Svenska Akeriforbundet, the Swedish Road Haulage Association. For Len Bassett this was a particularly interesting part of the study tour for he was able to compare and contrast the Swedish Association with our own RHA, of which he is a member.

Hans Stramberg, deputy editor of Lastbilen, the Association's journal, outlined its organisation for us. Its purpose is to "promote the development of the Swedish haulage contracting industry and safeguard and support the interests of its members." One of its most important tasks is to monitor and influence the political development of traffic and industrial policy, partly by extensive contact with the authorities and organisations for example regarding road, tax and company issues.

It was interesting to learn that even without prolonged lobbying from the Association, legislation to increase the maximum permitted vehicle width in Sweden from 2.5 to 2.6m had recently passed through the Swedish Parliament in only a matter of months. The increase in width was needed to allow containers to be carried in insulated bodywork.

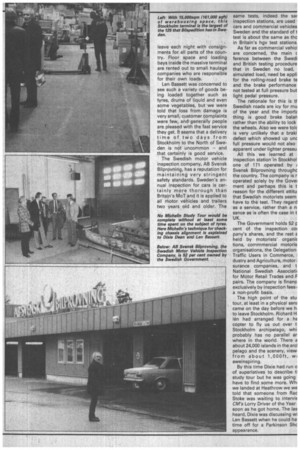

We learned that one of the main differences between the RHA and its Swedish counterpart is that SA has a central purchasing company, Saifa AB, which is run in regions with about 30 service facilities and order placement offices, run under their own management or in collaboration with the haulage contractor associations and companies. Products bought and handled for the haulag contractors include fuel, lubr cants and tyres, as well a various accessories and vehicl equipment. The company SA arrange( for us to visit was Bilspeditior one of the three biggest trans port concerns in Sweden. Rathe than owning its own vehicle Bilspedition is a transport e> change agency that provide work and warehousing for man smaller operators. It was surprit ing to hear that as many as 7 per cent of the road haulag contractors in Sweden are singl lorry companies.

In 1960, there were some 40 central haulage agencies in SWE den, but by 1979 Hans told u that the number had dropped ti 262, mainly as a result of sma agencies merging to form large ones. The Bilspedition terminE at Lunda, just outsidi Stockholm, is the largest of till company's 125 terminal throughout Sweden. TWI hundred vehicles arrive and 201

leave each night with consignments for all parts of the country. Floor space and loading bays inside the massive terminal are rented out to small haulage companies who are responsible for their own loads.

Len Bassett was concerned to see such a variety of goods being loaded together such as tyres, drums of liquid and even some vegetables, but we were told that loss from damage is very small, customer complaints were few, and generally people are pleased with the fast service they get. It seems that a delivery time of two days from Stockholm to the North of Sweden is not uncommon — and that certainly is good service.

The Swedish motor vehicle inspection company, AS Svensk Bilprovning, has a reputation for maintaining very stringent safety standards. Sweden's annual inspection for cars is certainly more thorough than Britain's MoT and it is applied to all motor vehicles and trailers two years old and older. The same tests, indeed the sar inspection stations, are used cars and commercial vehicles Sweden and the standard of t test is about the same as thc in Britain's hgv test stations.

As far as commercial vehicl are concerned, the main c ference between the Swedi and British testing procedure that in Sweden no load, simulated load, need be appli for the rolling-road brake to and the brake performance not tested at full pressure but light pedal pressure.

The rationale for this is if Swedish roads are icy for mu of the year and the imports thing is good brake balan rather than the ability to lock the wheels. Also we were tolc is very unlikely that a braki defect which showed up unc full pressure would not also apparent under lighter pressu All this we learned at inspection station in Stockhol one of 171 operated by Svensk Bilprovning throughc the country. The company is r operated solely by the Govei ment and perhaps this is t reason for the different attitu that Swedish motorists seem have to the test. They regard as a service, rather than a n sance as is often the case in t UK.

The Government holds 52 r cent of the inspection coi pany's shares, and the rest e. held by motorists' organiE tions, commmercial rnotoris organisations, the Delegation Traffic Users in Commerce, I clustry and Agriculture, motor i surance companies, and t National Swedish Associath for Motor Retail Trades and F pairs. The company is finaric exclusively by inspection fees a non-profit basis.

The high point of the stu. tour, at least in a physical sen.1 came on the day before we h. to leave Stockholm. Richard H. len had arranged for a he copter to fly us out over t Stockholm archipelago, whi probably has no parallel ar where in the world. There a about 24,000 islands in the arcl pelago and the scenery, view, from about 1,0 0 Oft, wi aweinspiring.

By this time Dixie had run o of superlatives to describe ti study tour but he was going have to find some more. Whi we landed at Heathrow we we told that someone from Rac Stoke was waiting to interviE C11,4's Lorry Driver of the Year soon as he got home. The las heard, Dixie was discussing wi Len Bassett when he could ha. time off for a Parkinson Shc appearance.