Damage to Roads from Extraordinary Traffic.*

Page 20

Page 21

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

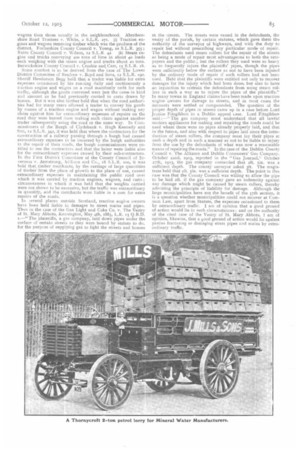

The great damage done to :cads and streets in burghs by extraordinary traffic has engaged the attention of municipalities for a number of years. In recent timesthe question has assumed a more or less acute form. Traction engine traffir: in burghs has increased enormously and, with the advent of heavy motor lorries for the cerriage of merchandise, street and road authorities are faced with the question of how far their streets and reads are capable of sustaining the enormous weights they are now called upon to bear and the destructive actirm of traction engines. The problem is, in a manner, a two-fold one. In the large cities it is chiefly the damage to streets, mostly causewayed streets, by traffic of extraordinary weight in police burghs it is chiefly the damage to roads, usually macadamised, by traction engines and their loads. So far as regards the carriage of merchandise by traction traffic, the ordinary well-made street should be capable of carrying heavy loads, but, when streets are called upon to bear heavy 'boilers and machinery or similar articles, it is obvious that local authorities being hound to provide safe highways for such traffic will have to construct streets very differently from the present streets, and to face the expenditure of large sums of money. The liability to damage from heavy weights is much accentuated by the presence of water, gas, electric and sewer mains and pipes passing underneath the streets, and not only expense to the authority is incurred, but great danger to the health of the community is created by the fracture of these pipes and the consequent escape of noxious and dangerous elements. The law as to recovery of the cost of repairing damage to streets is, broadly speaking, in an unsettled condition. A review of reported cases in both English and Scottish Courts discloses considerable diversity of opinion. These cases are noticed later.

Section 57 of the Roads and Bridges Act, 1878, provides for the summary recovery of extraordinary expenses incurred by the road authority in repairing highways by reason of damage caused by excessive weight passing along the same or by extraordinary traffic thereon. Section 3 of that Act defines " high• way " as including inter aiia all public streets and roads within any burgh or police burgh not at the commencement of this Act vested in the local authority thereof, but it does not include any street or road so vested, or any street, road or bridge which any person at the commencement of the -Act is bound to maintain at his own expense. By the Reads and Streets in Police Burghs (Scotland) Act, regi, laity alia police burghs are authorised to undertake the management and maintenance of the highways within the burgh, and I understand most police burghs in Scotland have availed themselves of this power.

The Locomotive _Acts impose restrict ions as to the wheels, weight and width of locomotives, and the Locomotive Act, 1861, enables local authorities to prohibit locomotives from driving over certain bridges and provides that, if a bridge or arch be damaged thereby, such damage may be repaired and the expense thereof recovered from the guilty party. Section 12 01 the i86x Act also contains this proviso :—" . . . nothing herein contained shall affect the right of any person to recover damages in respect of any injury he may have sustained in consequence of the use of a locomotive." Apart from these provisions no assistance is got from the Locomotive Acts. So far as I have learned no burghal authorities in Scotland possess special powers of dealing with this matter. In England this, however, is not the case, for at least in four towns the municipalities possess the power to compel the person damaging the streets by traction engine traffic to recoup them the outlays incurred. These towns are Birkenhead, Bury, Carlisle and Huddersfield. The three lastnamed towns have powers in identical terms, viz. :—" The Corporation may require any person who desires to use a traction engine in any street to deposit with them such sum of money not exceeding One hundred pounds as they may deem reasonable to recoup them the cost of repairing any damage which may be caused to any street or tramway by any such engine passing along or over the same respectively, and, in case of any such damage, they may repair the same and apply such deposit to meet, as far as it will extend, the cost of such repair, and may recover the balance of such cost from such person, and so from time to time."

Dundee, in common with other cities and towns, has suffered flora the consequence of heavy traffic over its streets, and some years ago the council decided to raise an action in the Court of Session, against a local engineering company, claiming damages for the destruction of the surface of streets and breaking of man holes and gas and water pipes. The enormous loads, which the streets were called upon to carry is shown by the fact that in one instance a boiler weighing 85 tons placed on a trolley weigh

ing 20 tons was hauled by three traction engines through the streets of the city for a distance of about a mile and a half. After accomplishing about a mile of the journey, and while traversing one of the principal thoroughfares of the city, a wheel of the trolley suddenly sank through the surface of the street, and the cavalcade was brought to a standstill. The combined efforts of four traction engines failed to move the trolley and boiler, and it was only after five traction engines had been requisitioned that the ponderous load was lodged at the harbour. The damage to the streets and to the tramway rails and gas and water mains was extensive. Following upon this, the council sent an account for the damage done to the engineering company, which repudiated the claim, and an action was raised in the Court of Session to have the liability fixed. For various reasons, however, one being that the company offered to pay £220, and also to come under an obligation to use in future a specially-constructed trolley with beechwooci covering over the wheels, the case was withdrawn. In the large cities, speaking generally, the streets were vested in the towns prior to the Roads and Bridges Act, and in Dundee and, doubtless, in Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen, the 57th Section of the Act does not apply, but in the police burghs it is, of course, operative. The Sheriff Court decisions on the point as to what constitutes extraordinary traffic under Section 57 of the Roads and Bridges Act form interesting reading, and a perusal of them leads one to the conclusion that burgh authorities will require to have a strong case before going into court. For one thing, it is not always easy for the road surveyor to make pp a claim which could stand investigation in the Law Courts, and, further, the sheriffs, whose decisions are final, seem, generally speaking, to side with the offenders. Before giving a short review of cases regarding extraordinary traffic, let me quote what perhaps is as. gooda definition of extraordinary traffic as can be given. I quote from the case of Hill v. Thomas, 1893. The Court of Appeal laid down this rule :—" Extraordinary traffic is really a carriage of articles over the road at either one or more times which is so exceptional in the quality or quantity of articles carried or in the mode or time of user of the road as substantially to alter and increase the burden imposed by ordinary traffic on the road and to cause damage and expense thereby beyond what is common." In this case L. J. Bowen lays down that the object of the section is not to prohibit or penalise extraordinary traffic, brit to lay the extra expense of damage done by such thine to the road on the right shoulders, viz., upon those whocaused the damage and to whose be.nefit it enured. I give a short summary of a few of these cases and first the few cases• where the traffic was held to be extraordinary traffic :--(a) Traction engine and two wagons with materials for the ordinary purposes of an estate and exceeding 4 tons. Lord Aveland v. Lucas, 1879, 5 C.P.D., 211. (b) Manure conveyed by engines and trucks 13 tons in weight on a road communicating with twohighways, the road being used principally for farm traffic, but the highways being suitable for engines. Queen v. Ellis, 1882, 8 Q.B.D. 466. (c) Held that the carriage of 8,o5o tons of shingle arid cement in .9,000 ordinary eartloads, whereby road was cut up so as to require extra repairs, was extraordinary traffic. Inn and Co. V. Thomas. Court of Appeal (1.. 3J. Bowen and Kay, August moth, 1893. (d) Carting of 6,423 tonsof stones in two years along narrow farm road. 16 S.L.R. 43. On the other hand the following have been held not to beextraordinary traffic :—(a) Carriage of timber grown in the district blown down by an exceptionally severe gale and conveyed in four-wheeled wagons, a load weighing from a} to 51 tons. Berwicknhire Road Trustees v. Martin, i S.I.R. 387. ' (6) Stoneconveyed from a quarry in loads 44 tons to 6 tons in weight and drawn by three horses, such traffic being a recognised business in the neighbourhood, and the loads of the usual weight. in such traffic. Wallington v. Hoskins, 188o, 6 Q.B.D. 2o6. (c) Materials for building a house carried in wagons weighing from 30 to 35cwt. with two or three horses and a drag, theordinary traffic being light agricultural traffic. Pickering, etc., Highway Board v. Barry, 1881, 8 Q.B.D. 59. (d) Traffic from a quarry in. excess of the traffic which any other person put upon the road. Arbroath Road Trustees v. Murray and Mann, 1882, Sheriff Court of Forfarshire. (ei Manufacturing traffic which had formerly been carried by ittilway. Aberdeen Burgh Road Trust v. Alex. Pirie and Sons, Ltd., i882; Sheriff Court of Aberdeen. (f) Traffic from Granite W (irks, Kirkcudbright Road Trustees v. Shearer Field and Co. ; Sheriff Court of Kirkcudbright. (g) Mineral traffic carted to railway station, though most of pits in district had direct communication with railway. AyrshireRoad Trustees v. Dunlop and Co., 2 S.L.R. 254. (h) Traffic not extraordinary in the sense of the Roads and Bridges Act so as to impose liability for the whole cost occasioned by it merely because it is carried on by means of locomotives and by heavier wagons than those usually in the neighbourhood. Aberdeenshire Road Trustees v. White, 2 S.L.R. 271. (i) Traction engines and wagons removing timber which was the produce of the district. Forfarshire County Council v. Young, io S.L.R. 355; Nairn County Council v. N‘ilson, 12 SL .R. 42. (k) Steam engine and trucks conveying 200 tons of lime in about 40 loads each weighing with the steam engine and trucks about ao tons. Berwickshire County Council v. Crosbie and Carr, 15 S.L.R. is.

Some comfort is to be derived from the case of The Lower District Committee of Renfrew v. Boyd and Sons, re S.L.R. Igo. Sheriff Henderson Begg held that a trader was liable for extra expenses occasioned by his runaing daily and continuously a ti action. engine and wagon on a road manifestly unfit for such traffic, although the goods conveyed were just the tame in kind and amount as he had previously carried in carts drawn by horses. But it was also further held that when the road authorities had for many years allowed a trader to convey his goods by means of a traction engine and wagon without malting any claim against him for extraordinary expenses of repairs on the road they were barred from making such claim against another trader subsequently using the road in the same way. In Commissioners of the Burgh of Clydebank v. Hugh Kennedy and Son, 12 S.L.R. 342, it was held that where the contractors for the construction of a railway passing through a burgh had caused extraordinary expenses to be incurred by the burgh authorities in the repair of their roads, the burgh commissioners were entitled to sue the contractors and that the latter were liable also fcr the extraordinary expenses caused by their sub-contractors. In the First District Committee of the County Council of Inverness v. Armstrong, .kddison and Co., IS S.L.R. roo, it was held that timber merchants, by the carriage of large quantities of timber from the place of growth to the place of use, caused extraordinary expenses in maintaining the public road over which it was carried by traction engines, wagons, and carts ; circumstances in which it was held that the weights carried were not shown to be excessive, but the traffic was extraordinary in quantity, and the merchants were liable in a sum for extra repairs of the roads.

In t7everal places outside Scotland, traction engine owners have been held liable in damages to street mains and pipes. Thus iii the case of the Gas Light and Coke Co. v. The Vestry of St. Mary Abbots., Kensington, May 4th, 18,85, L.R. 15 Q.E.D. z.—" The plaintiffs, a gas company, laid down pipes under the surface of certain streets as they were bound by statute to do, for the purpose of supplying gas to light the streets and houses in the ttroets. The streets were vested in the defendants, the vestry of the parish, by certain statutes, which gave them the authority of the surveyor of highways, and with, the duty to repair but without prescribing any particular mode of repair. The defendants used steam rollers for the repair of the streets as being a mode of repair most advantageous to both the ratepayers and the public ; but the rollers they used were so heavy as to frequently injure the plaintiffs' pipes, though the pipes were sufficiently below the surface as not to have been injured by the ordinary mode of repair if such rollers had not been used. Held that the plaintiffs were entitled not only to recover damages for the injury which had been done, but also to have an injunction to iestrain the defendants from using steam rollers in such a way as to injure the pipes of the plaintiffs." In many towns in England claims have been made upon traction engine owners for damage to streets, and in most cases the accounts were settled or compounded. The question of the proper depth of pipes in streets came up in a case before Lord Justice Fitzgibbon in a Dublin appeal case. Lord Fitzgibbon said:—" The gas company must understand that all lawful modern appliances for making and repairing the roads could be used where there were no pipes already properly laid, and that in the haute, and also with respect to pipes laid since the introduction of steam rollers, the company must lay their pipes at such a depth and in such a manner as not to be liable to injury from the use by the defendants of what was now a reasonable means of repairing the roads." In the case of the Dublin County Council v. The Alliance and Dublin Consumers' Gas Company, October 22nd, 1003, reported in the "Gas Journal," October 27th, 1903, the gas company contended that 2ft. 5in. was a sufficient depth. The county surveyor asked 3ft. The magistrate held that aft. 51n. was a sufficient depth. The point in this rase was that the County Council was willing to allow the pipe to be laid aft, if the gas company gave an indemnity against any damage which might be caused by steam rollers, thereby admitting the principle of liability for damage. Although the large municipalities have not the benefit of the 57th section, it is a question whether municipalities could not recover at Common Law, apart from Statute, the expenses occasioned to them by extraordinary traffic. I am of opinion that a good ground of action would lie in such circumstances: and on the authority of the cited case of the Vestry of St. Mary Abbots, I am of opinion, likewise, that a good ground of action would lie against parties fracturing or damaging street pipes and mains by extraordinary traffic.