Road Test of Albion Viking -Alexander Bus

Page 121

Page 122

Page 123

Page 127

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

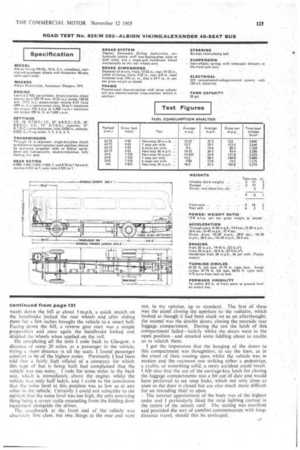

IN the early spring of 1923 the Albion Motor Car Co. Ltd. of Scotstoun, Glasgow, produced its first Viking motorcoach. From then until the present day there has been included in the range of vehicles manufactured by this company a passenger chassis bearing this name. The differences between that first Viking and the presentday vehicle are of such magnitude that only the famous Albion badge now points to the origin of the vehicle. It is true to say, however, that whilst the appearance of .the vehicle has changed, the inbuilt quality that for many years has been a feature of the Albion has not.

Designed to satisfy all the requirements of the presentday passenger service vehicle, the Viking—which was fully described in The Commercial Motor, July 2 this year—is a rear-engined chassis, having its steering axle set back from the front-end enough to accept forward-entrance bodywork. It is powered by the Leyland 0.400 six-cylinder, direct-injection, overhead-valve, four-stroke diesel engine, driving through a 16 in.-diameter, single-dry-plate clutch and an Albion five-speed and overdrive gearbox to the hub-reduction rear axle.

The engine is mounted longitudinally and vertically between the main frame members behind the rear axle, leaving the wholeof the chassis frame from a point 4 ft. 1-1in. from the rearmost extremity completely clear to accept bodywork of 40to 45-seat capacity. Suspension is of conventional design in that semi-elliptic leaf-springs are used at both front and rear axles. However, a lot of attention has been paid to obtaining the most comfortable riding characteristics in all conditions of loading and the front springs are no less than 54 in. long, whilst the rear ones are 60 in. long., Telescopic dampers arefitted to the front axle only.

A dual-circuit braking system is incorporated in the vehicle, and is one of the outstanding features of the machine. This takes the form of two completely separate braking systems, one serving the front-axle brakes and one the rear-axle brakes. Two separate reservoirs are linked through a dual brake valve to Clayton Dewandre air-overhydraulic units, powering Girling two-leading-shoe assemblies at both axles. Thus, in the event of a failure occurring in either circuit, full braking is still available on the remaining axle, enabling a driver to bring the vehicle safely to rest. The handbrake is of the single-pull variety operating on the rear wheels only.

When a test on the Albion Viking was carried out by The Commercial Motor recently, it was of a chassis bodied by Walter Alexander and Co. (Coachbuilders) Ltd., of Falkirk, Scotland. The chassis was a prototype and had just previously been fitted with a 16 in.-diameter clutch assembly in place of the standard 14 in. unit which had in service been found incapable of providing long life. I must admit that the tendency for the engine to take a long time to die down, and the fact that the clutch "spun on" for a few seconds when trying to engage a gear from standstill, caused me some embarrassment when first driving the vehicle. However, it proved to be a matter of getting used to a 3.5 sec. delay whilst the engine died and, after the first hour, gear-changing was no longer a problem.

I do feel that this point is one that needs urgent attention, especially should the vehicle be placed into service in either an extremely hilly district or a heavily trafficked area, where I have no doubt that the gearbox would come in for an enormous amount of punishment during the stopstart day of a stage service bus. To any driver who has never before handled a rear-engined vehicle, the first impression is that there is something missing. And it takes some time to get used to the fact that if you need to listen to the engine to assist in gearchanging, you must do so through the side window of the driving compartment and, even then, extremely carefully.

One of the side effects of having the engine so far away from the driver is a sense of lack of power, and I found personally that this feeling was not dispelled until we carried out the acceleration tests, and the oneand sixstops-per-mile tests when the results proved that the performance of the vehicle was completely adequate.

The test took place in an area north-east of Glasgow and this entailed, on two days, travelling out from the city to Buchlyvie on the south-western end of the Kippen Strait. This stretch of road, which runs east towards Stirling, is of undulating character-for the first five miles and completely straight and flat for the remainder. It was used to achieve the acceleration, fuel consumption and braking figures contained in this report. The trip out from Glasgow on each day entailed running 35 miles along second-class A roads which over most of the distance consist of two traffic lanes. During these journeys I had plenty of time -to assess the qualities of steering and general handling of the machine. Whilst the former was excellent at all times, I gained the impression that operating pressures on the clutch and brake pedals could, with advantage, have been lower than they were. This, coupled with a fairly heavy gear change, made handling of the machine somewhat tiring. But, once rolling on an open road the nicely loaded throttle pedal and extremely light steering about evened up the score. 1 particularly liked the excellent driving position afforded to the driver. Most controls are well placed, coming easily to hand without the need to stretch oneself unduly. The only exception to this. is, the gear lever, which has rather. a long travel from firstto second-gear positions. When one thinks in terms of the number of gear changes that are made by a service-bus driver during each working day of, say, 10 hours, the staggering figure of 2,400 represents the minimum number if he covers 100 miles at six stops per mile. In all probability it will be a good deal more than this if his duty is in a congested city. In these conditions, that "extra stretch" becomes a heavy load to bear, and remember that there are two clutch movements to every gear change. It will be obvious that these figures represent upward changes only, and only those concerned with the actual stops.

Although tiny by comparison with much of the mirror equipment fitted to vehicles today, the round convex mirrors on this vehicle are good, giving a complete picture of what is going on around the machine, but creating none of the blind spots caused by the larger types. The screenwipers, having received a good deal of thought in their positioning, clear a respectable area of the screen where it is most needed, making driving in dirty conditions much less arduous.

Fuel consumption tests proved to be extremely satisfactory, with the vehicle returning 13.6 m.p.g. at 30 m.p.h. non-stop. This test was, in fact, carried out at rather a fast speed, the average being 31.2 m.p.h. At one stop per mile at an average speed of 29.1 m.p.h. the fuel consumption proved to be 12.7 m.p.g. At six stops per mile, making an average speed of 14.6 m.p.h., the fuel consumption was 9.2 m.p.g. These were the fully laden tests. Half laden, the fuel consumption at six stops per mile varied very little. At an average speed of 15.8 m.p.h. it was 9.9 m.p.g. One

stop per mile at an average of 28.4 m.p.h. returned a consumption of 14-3 m.p.g., and non-stop at an average of 33 m.p.h. returned 14-6 m.p.g.

Cruising at 32.2 m.p.h. average with the vehicle unladen returned a fuel consumption of 18-2 m.p.g. and fully laden at 40 m.p.h., making an average speed of 36-35 m.p.h. and consumption of 10.3 m.p.g. The absence of a motorway prevented me from carrying out a full-throttle test owing to continual baulking by other vehicles on the narrow roads. It was during the six-stopsper-mile fuel-consumption tests that the rather excessively heavy clutch and footbrake pressures were most noticed. When these pressures were checked with a pressometer they proved to be 75 lb. and 110 lb. respectively, somewhat heavier than is desirable for this type of operation.

Average times taken during the acceleration tests were surprising. This was because (as I mentioned earlier) of the impression I gained that the vehicle was somewhat sluggish. Accelerating through the gears from 0 to 20 m.p.h. in 14.5 sec., from 0 to 30 m.p.h. in 26.6 sec. and from 0 to 40 m.p.h. in 47-4 sec., it was in fact better than I had expected.

I have no doubt that quite a few seconds were lost during these tests through the extremely slow gear change. The vehicle would probably have performed quite a bit better had the axle ratio been lower than the one fitted, which was 5.5 to 1.

If I could fault the qualities of the machine with regard to acceleration I certainly could not do so with regard to

braking. This, during all the full-pressure stops made, was extremely positive and accurate, the overall figures being, from 20 m.p.h., an average braking distance of 1945. ft.-that is, 22 ft/s2 retardation, and from 301n.p.h. an average distance of 44.3 ft., or 21-9 ft/s2 retardation. The average Tapley reading for all these stops was 86 per cent.

The handbrake. which I have already said is of the• single-pull variety, produced an average Tapley meter reading of 36 per cent. On nearly all the stops made there was_ some evidence of wheel-locking but at no time did the vehicle tend to slide more than a few inches off the chosen course. The one surprising point of the whole test was the almost complete lack of fade, apparent when the brake fade test was carried out later on.

Using a hill 3-5 miles long and with an average gradient of 1 in 16 and a maximum gradient of I in 5, the hill climb was carried out in an ambient temperature of 13°C (55°F). The engine cOolant temperature at the start of the climb was 76-C (170°F) and on reaching the top this had risen only 3'C to 79°C (176°F). During a total time of 11 min. 5 sec. taken to climb the hill, third gear—which was the lowest used--was engaged for 2 min. 32 sec.; the minimum speed recorded was 12 m.p.h. The road used was the B822 from Fintry to Lennoxtown, over the Campsie Hills.

On the descent from Campsie Muir—which is the highest point—to Lennoxtown, the average gradient is 1 in 16 and the distance approximately 2.6 miles. This -was covered at an average speed of 25 m.p.h. with direct top-gear engaged, when a continual application of the footbrake was required to restrict the vehicle to this speed.

It will be seen that this is an extremely severe test of braking equipment, and I was agreeably surprised when doing a full-pressure stop from 20 m.p.h. on the only 100 yards of level road for miles around immediately at the bottom of the gradient, that the Tapley _meter gave a reading of 71 per cent. This was only. 15 per cent lower than the average figure recorded during the brake test.

To assess the capabilities of the vehicle, with regard to stopping and starting on a severe gradient, a short local hill in Glasgow was chosen, which at its steepest point is 1 in 5. I found it impossible to achieve a second-gear start whilst facing up the hill, but first gear accomplished this easily. Once again the braking, equipment proved to be excellent. When allowing the machine to run back wards down the hill at about 5 m.p.h. a quick. snatch on the handbrake locked the rear wheels and after sliding them for a few inches brought the vehicle to a smart halt. Facing down the hill, a reverse gear start was a simple proposition and once again the handbrake locked and skidded the wheels when applied on the roll.

On completing all the tests I rode back to Glasgow, a distance of some 20 miles, as a passenger in the vehicle, trying a short distance in all the seats. I found passenger comfort to be of the highest order. Previously I had been told that a fairly high official of a company for which this type of bus is being' built had complained that the vehicle was too noisy. I rode for some miles in the back seat, which is immediately above the engine, whilst the vehicle was only half laden, and I came to the conclusion that tile noise level at this position was as low as at any other in the vehicle. Certainly I couldnot subscribe to the opinion that the noise level was too high, the only annoying thing being a severe rattle emanating from the folding door equipment alongside the driver.

The coachwork at the front end of the vehicle was. absnlweiy first class, hut two things at the rear end were

not, in My opinion, Up to standard. The first of these was the panel closing the aperture to the radiator, which looked as though it had been stuck on as an afterthought; the second was the double doors, closing the nearside rear' luggage compartment. During the test the latch of this compartment failed-luckily whilst the doors were in the open position-and entailed some fiddling about to enable us to relatch them,

I got the impression that the hanging of the doors to this compartment was thoughtless, to say the least, as in the event of their .coming open Whilst the vehicle was in motion and the rearmost one striking either a pedestrian, a cyclist, or something solid, a nasty accident could 'result. .1 felt also that the use of the carriage-key, latch for closing the luggage compartments was a bit out of date and would have preferred to see snap locks, which not only close as soon as the door is closed but are-also much more difficult

for an intending thief.to open. .

. The interior appointment of the body was of the highest order, and I particularly liked the strip lighting carried in the centre of the saloon roof. The seating Was excellent and provided the sort of comfort commensurate with longdistance travel, should this be envisaged....