A Model Maintenance System

Page 30

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 36

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THE keenest interest is always shown in the articles of this series which deal with schemes and methods of maintenance. That subject vies with costing in its claim for the attention of readers, The subject of maintenance is controversial. too, in several of its aspects, particularly as to whether it is better for the operator himself to take care of his vehicles or to place the work in the hands of a local garage proprietor. Alternatively, there is a difference of opinion as to whether maintenance should be preventive or curative.

Whether maintenance should be carried out by the operator or by a local garage, depends, I have always felt, on the circumstances ot the case. An important consideration is whether the fleet is big enough to justify the employment of the necessary staff, the use of part of a building and the purchase of equipment. Sometimes another factor enters, and that relates to the facilities available in local garages and if they be the kind to satisfy the needs of the heavy-vehicle operator.

It is true that preventive maintenance cart sometimes be costly. All that is needed in order to put it on a commercial and economical basis is. however, the use of discretion in the. application of preventive maintenance. This discretion usually evolves into careful consideration of the scheme and its possible modification from time to time, as experience shows to be needful, but there is confirniation of my view that the matter cannot be decided arbitrarily but must turn on the circumstances in the variety of maintenance systems which are in force, and all of which are apparently proving satisfactory to those who operate them.

I have lately received a letter from a Cornish friend of mine which delineates a system of maintenance for a small fleet and is as good as any I have seen. It forms the main subject of this article. It is particularly interesting inasmuch as it has a bearing on all the controversial points mentioned above, in that it is devised to meet special circumstances of operation, and it answers the question of whether it. is preferable to do the maintenance at home or to go to the local garage. It is an example of preventive maintenance which, as the outcome of experience and application, has been reduced to a minimum of cost, and my friend demonstrates that a characteristic of maintenance enthusiasts is their willingness to give their experience for the benefit of all.

Before proceeding, it is perhaps important that I should give the status of this operator: he is actually in the main an agricultural merchant, miller and engineer. The system he recommends has the particular advantage that is the outcome of experience, having been first devised nearly two years ago, and it has recently been revised as the result of nearly two years' trial.

One of the difficulties he met at the beginning of the scheme made it awkward to keep it running. The reason for this was that some vehicles had been neglected for so long, because of labour shortage, that when they came up for a comprehensive check every four weeks, it was found that a complete overhaul was necessary.

Writing to me recently about his revised scheme, he said that some maintenance operations used to be scheduled for carrying out more often than was necessary, and there was a tendency for them to be skimped or even put aside. The result was that some jobs were left for longer than they should have been, and it was because of that he decided to revise the sequence of the routine.

He lays down a fundamental principle of maintenance with which all who have any experience must agree. The purpose of maintenance is to provide that the vehicle concerned is off the road for the minimum period of its life and never off involuntarily except in the case of accident.

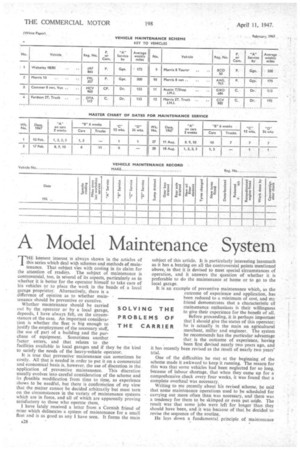

Here is the scheme which I propose to describe briefly in reference to the accompanying schedules which, as a matter of fact, are almost self-explanatory.

There are four schedules, A, B, C. and D. For convenience of internal operation these are printed on different-coloured paper, as is indicated in the accompanying reproductions.

Schedule A is of operations which, so far as the lorries are concerned, are to be carried out weekly. The application to the ordinary motorcars and utility vehicles, which are part of the fleet, is fortnightly. In the case of the lorries, the work is done by the drivers: cars are taken care of by the garage.

Reading Schedule A, the experienced operator will come, I think, to the conclusion that it comprises just those small jobs which should be done not less than once a week. Incidentally, the mileage covered by each vehicle is indicated on one of the accompanying schedules, which is entitled "Key to Vehicles."

Systematic Greasing Of particular interest is the way in which, in the section referring to greasing, the number of points is specifically enumerated, and the drivers or garage mechanics, as the case may be, are expected to check off each series as they go through the work, thus making sure that none of these important lubricating points is overlooked.

It is just as well to note that on this schedule there is provision for the driver to record that he has done this maintenance either in the company's time or his own. There is space for him to record the time taken and for the entry to be countersigned by the foreman, the reason being that the driver is paid a bonus for doing this work.

To all the schedules the following important features are common:—First, provision for a tick in the appropriate column to indicate that the work has actually been done: second, provision for recording the condition of the part concerned; third, space for remarks. Then, at the bottom, there is a space for a note of spares which are needed or have -been used, presumably from stock, and for a note of the action taken as regards those spares. These are good points, as also is the footnote that mechanics must always give the vehicle number on the time sheet against the time spent.

It is of interest to note that, in the B service, the first item provides for the mechanic to cheek that the A service has been effectively rendered during the intervening six weeks. A similar provision is made in reference to C,

A Thorough Examination Sheet D budgets for a complete check of the vehicle throughout. The first operation is to take the vehicle on the road and make notes of its performance in reference to no fewer than nine points. There. is then a schedule of 16 operations, and thereafter the vehicle is again taken on the road and a further check made.

It is one thing to plan a schedule of service operations: it may be quite another to arrange matters so that those operations are carried out at the appropriate times in respect of each particular vehicle of the fleet.

The method of doing so in this case is shown in what is called the " Master Chart of Dates for Maintenance Service." It is here, at least, that I recognize a reference to articles published in "The Commercial Motor," for this is similar to a scheme that I devised, which appeared its this journal for August 31, 1945.

It is not easy to devise a plan such as this. It is necessary, for example, to be careful that a vehicle is not brought in more often than necessary. It would be absurd, for example, to be brought in for Operation B one week and the next week for Operation D. To plan the service does not mean merely allocating a vehicle to be brought in every six, 12 or 24 weeks. Vehicle No. 1, for example, undergoes, in the first week, operations A, B, C and D, and vehicle No. 7 in the 27th week is in for Operations B, C and D.

Finally, I must refer to the form marked "Vehicle Main

tenance Record" My informant tells me that for each vehicle there is a foolscap folder in which are filed all records of operations A, B, C and D, so that they may be referred to, when necessary, as a cheek not only that the work has been done, but on the frequency of need for the supply of certain spares and so on.

THE maintenance engineer's dream is about to come true, when engines will be re-born over-night without any special skill being required. "

The ideal engine should be fitted with valves in detachable cages. This was done years ago by one prominent manufacturer, and 1 see no reason why it should not be done to-day. After all, it is only the same as fitting a detachable seating for the valves.

The cylinder liners must be of the dry type and a push-in fit to the cylinder blocks, each with a flange at the top to sink into a recess in the block. These would be removable without the use of expensive tools, so that, instead of reboring the cylinder block, all that the maintenance staff would have to do would be to draw out the worn line's and fit new standard ones, complete with pistons. I also suggest a standard set of crankshaft liners or sleeves, after the type of bearing shells, to be located by a pair of dowels in the crankshaft, so that the oil-feed hole comes opposite the holes in the shells.

With these standard shells fitted, the crankshaft would be a standard shaft at all times, and therefore eliminate the expensive and long job of striPping an engine to remove the crankshaft for regrinding.

When the maintenance engineer gets all these simple fittings combined in one engine, his cares and worries will be considerably reduced.

Here is an example of the speeded repair service that would be achieved with such an engine, whether it be of the C.I. or 1.C. type: Vehicle A comes in from London with loss of power, heavy oil consumption and a faulty rear main bearing passing oil into the clutch housing. The maintenance men remove the cylinder head and the locking rings that hold the valve cages in position, and withdraw the valves complete with seats and springs. One man then proceeds to fit new cages or reground ones removed from a previous engine.

Fitter No. 2 detaches the engine oil sump and gives it to his labourer to clean out, while he takes off all the big-end bearing caps. When this is done, he draws out the cylinder liners complete with connecting rods and pistons, and dismantles them on the bench. The only parts he will require to use again will be the connecting rods. These are then fitted with new standard pistons and put into new cylinder liners ready to be replaced in the cylinder bores.

By this time No. I will have replaced the valves, No. 2 then slacks off all the main-bearing caps and allows the crankshaft to be lowered slightly, so that he can ease out the upper halves of the main-bearing shells. The new crankshaft-journal shells can now be fitted, as

each conies to the bottom when the shaft is rotated slowly. By doing this, the necessity of removing the crankshaft for a regrind is eliminated, and the crankshaft is still a standard size. All the journals are ready for new big-ends and main bearings to be replaced, as this standard-size finish should require no fitting.

No. 2, having got his crankshaft in position, complete with new main bearings, and nipped up tight. No. 1 then proceeds to insert the new push-in liners, complete ' with new pistons and connecting rods, which have previously been fitted into the bores on the bench. The connecting rods are then guided into position on the crankshaft, which has previously had new standard bigend journal sleeves (or shells) placed in position by No. 2 underneath the vehicle. He then proceeds to tighten the big-end bolts and lock them in place. The engine is now ready for cylinder head and engine sump to be placed in position.

Thus, the engine has been re-born in a fraction of the time usually taken to do the same amount of work, using the old method of regrinding the shaft.

With the adoption of this new method, the question of skilled fitting need not be considered, as there would be no undersized crankshafts or undersized bearings to be contended with.

When shall we see these simple improvements?

Perhaps soon. A. WOOD, M.I.R.T.E. Woolton, Liverpool.

EXPERIENCE OF OPERATION AT .\ 15,000 FT.

VESTERDAY I received my six-weeks-old copy of " The Commercial Motor" and noted with interest the letters and discussion on tyre sizes, and the effect when odd sizes are fitted on driving wheels.

On two or three occasions I have had to fit odd-sized tyres on some of our vehicles, tyres of any size being almost unobtainable out here, but I have never had complaints of overheating axle casings.

It may be of interest to you to know that we are operating petroland oil-engined vehicles at altitudes up to 15,000 ft., the petrol-engined vehicles having no other modification than the fitting of smaller jets, although there is a 40 per cent, power loss at this altitude and starting from cold requires use of the choke. The main trouble on the type of oil engine that we are operating is that of cooling, as water boils at 180 degrees F. at 15,000 ft. As the normal running temperature of the engine is slightly higher than this, we are experimenting with a pressure radiator and condenser.

would be grateful if you could send me the reports of the papers and discussions of the Institute of Road Transport Engineers, also particulars of membership. J. WHITELEY, Assistant Chief Diesel Engineer.

Lima, Peru. (For Ferrocarril Central del Peru.)

'Although it was not expressly stated, we think that any trouble with the overheating of driving axles through the fitting of tyres of slightly different sizes has occurred only where two axles have been arranged in bogie form. The reference to engine overheating when operating at high altitudes is particularly interesting, and it might be possible to fit a few more tubes to the radiator, although the engine would probably then be running at an inefficient temperature. It might also be possible to use some cooling medium with a higher boiling point, such as ethylene glycol, as employed in some aero engines. This would not only permit a much higher running temperature, but would obviate any danger of freezing if, at this height, frost occurs. 'We are sending you particulars of the 1.R.T.E., and such membership would give the right to receive reports of the meetings.---Fo.] THAT favourite Sussex watering place of Dr. Johnson's (called in his day Brighthelmstone) has always been conscious of a duty to please its visitors and its residents. This duty has been executed famously, and shared alike by the adjoining borough of Hove. The result approaches the model province, both for work and play.

Anyone who knows Brighton and Hove recalls with admiration the Royal Pavilion, the Hove Marina, the Brighton Aquarium, Preston Manor, -Booth Museum, the broad level esplanades and the great park areas ad recreation grounds. They remember countless places of entertainment—piers, cinemas, theatres, dance halls, concert halls, inns, etc. They have seen the big hotels, the shopping centre, the new housing estates and probably the two large electrical factories. Summer and winter alike, there is much activity within the boundaries of Brighton and Hove, as well as into and out of them.

In such circumstances, the system of public transport is of the greatest importance, whether it be operated by the local government or by a private company. Often we find both types of operator in a town. Sometimes they work with each other, sometimes against. It is difficult to imagine a municipal transport system more closely linked with a private bus company than in the case of Brighton.

The arrangement is of unusual interest and came about as the result of a succession of different alliances, and attempted alliances, over many years. Let us go back to 1884, when the first effort at co-ordination was the formation of the Brighton,_ Hove and Preston United Omnibus Co., Ltd., from small companies of horsed-bus operators. By 1904 both Brighton Corporation and that company were in the picture, the former with trams running approximately north and south, the latter with motorbuses running roughly east and west.

The Kaiser war brought Thos. Tilling, Ltd., on to the scene. This company purchased the Brighton, Hove and Preston United Co., and a former agreement between B.H. and P.U. and Southdown Motor Services, Ltd., for longer services, was now assumed by Thos. Tilling, Ltd.

Later, agreement was reached with Brighton and Hove Corporations, whereby the company would give services on approved routes and the corporations would not exercise or lease their powers. Under this agreement the company paid both Brighton and Hove Corporations the sum of £40 per annum in respect of each bus operated, with a minimum of 50 buses. In 1932 the Traffic Commissioners vetoed the payments, under the Road Traffic Act, 1930, and ordered that the equivalent annual sum should be passed on to the public by way of reduced fares.

In 1929 a transport board, merging the services of Thos. Tilling, Ltd., and those of Brighton Corporation, on the lines of London . Transport, was proposed, and rejected by the ratepayers. In 1932 a similar plan modified in some details was once more rejected, this time both by the ratepayers and the Minister of Transport. The year 1935 saw the formation of the Brighton, Hove and District Omnibus Co., Ltd., as a Tilling subsidiary, and this company took over the Brighton and Hove section of Thos. Tilling, Ltd. Four years later, the present co-ordinated system, which is a pool of corporation and company operation, came into force.

The company provides and operates vehicles to cover 724 per cent. of the total vehicle mileage of the pool, whilst Brighton Corporation takes care of the balance of 27i per cent. The Brighton municipal fleet consists of 19 motorbuses and 44 trolleybuses, and the company fleet of 8 trolleybuses and 137 motorbuses, so that each party operates both forms of transport. The district served covers the boroughs of Brighton and Hove, whilst Southdown Motor Services, Ltd., operates long-distance services radiating from Brighton.

Having drawn a descriptive blueprint of the transport set-up in the twin boroughs, I should like to go into details of the company-operated part of this unusually efficient machine, as I saw it a week or two ago.

main bearing borer, Cuthbert con-rod borer, Archdale radial drill, several medium-sized lathes, and a specially adapted Bradbury machine for boring out brake drums.

In connection with the last-named, the system of brake reconditioning needs special mention. Drums, when worn, are not simply skimmed out, but are bored to take liners of high-carbon spring steel. These are secured in the drums by countersunk rivets and are then cleaned up to a standard size. Before final boring, the drums are mounted on their hubs and shafts in order to ensure concentricity. To all intents and purposes, brake drums have an indefinite life.

Maintenance is carried out on a time and mileage basis. Thus there are nightly inspections, during which brakes and steering, clutch and other components are checked and corrected, general topping-up is carried out and grease is injected where needed. Every three to four weeks there is a routine examination for each

vehicle, occupying about four hours. On a mileage basis there is a medium overhaul at 50,000-60,000 miles The motorbus fleet of the Brighton, Hove and District. Omnibus Co., Ltd., is almost 100 per cent. oiler. There are 102 Bristol and A.E.0 vehicles fitted with Gardner engines, two new Bristol K6Bs (and seven more to be delivered), and 33 A.E.C.s with 7.7-litre engines. All are double-deckers, except two petrol-engined vehicles. In addition, there are eight trolleybuses with 80 h.p. motors, whilst three more are to be delivered this year. These will have 120 h.p. motors to allow a greater efficiency margin on the abnormally hilly parts of the routes.

Many older buses have been converted from petrol to oil over a period of years, the last conversion having been made recently. A certain number of 52-seater open-staircase Regents has been operated, but these vehicles are gradually being replaced or converted. On the sea-front service, open-top buses in'cream livery are used.

The company has a particularly fine engineering department in Conway Street, Hove, under the control of the chief engineer, Mr. T. G. Pruett, A.M.I.A.E. I was taken around -the shops by his technical assistant, Mr. R. 0. Blatchford, a keen young student of mechanical engineering. The works and office block were built and occupied just before 1939.

In the machine shop are the following tools:—Heald cylinder grinder, Dean Smith and Grace 15-ft lathe, Jones and Shipman drilling machines adapted for brake refacing operations, Denbigh horizontal miller, Cuthbert

and a major overhaul at 100,000-120,000. miles. The former is a top and bottom overhaul, with partial stripping and examination of certain chassis parts (such as axle shafts, which are put on a crack-detector), and renewal of rings or pistons if needed. The major overhaul is a complete overhaul of all parts, including the body.

Cylinders are bored 40-thou. oversize in the case of Gardners and 1 mm. in the case of A.E.C.s. Crank regrinds are carried out by Southdown Motor Services, Ltd. There is a single-pin crank regrinder in the workshop equipment which is used only in cases where an odd pin or two requite grinding. There is a good deal of reclaiming of parts by building up, Stelilting, etc.

Body repairs of an extensive nature are carried out and at the present time van bodies are being built for Thos. Tilling, Ltd.

Incorporated in the engineering department are modern electrical, blacksmith's, welding and tinman's and other shops, and there is a well-stocked stores.

I noticed that the oil-engine pump-room was laboratory-like and scrupulously clean, as should be the case in any good workshops. There were the usual items of equipment, including a Hartfidge test bench, and one or two special items, such as a Hartridge nozzle tester which simulates Tvorking conditions more closely than the older lever type. A Hartridge fuel-pump vice. is a valuable addition to the equipment, and there is an electric lens-light for the close examination of nozzles. Oil reclamation is systematic, there being both Seagull and Streamline units; the former filters 15 gallons a day. The oil is preheated in a large tank, in which a large amount of presettling or filtering takes place, and thus increases the output of the main filters. Degreasing plant is of the I.C.I. het type.

The staff position is relatively good in the department, there still being many skilled hands of long service. There is an apprenticeship scheme which is most comprehensive, although the boys are not indentured. Their first six months are spent in the stores, after which they go either to the body shop or machine shop, according to their preference and bent. They attend the Technical School during working hours. This system has been in fOrce for many years.

Accommodation for Vehicles Garage accommodation is provided for 60 buses at Conway Street and for a further 80 at Whitehawk Garage, situated in the Black Rock district in Brighton, where trolleybuses are also garaged. The last-mentioned operate from there and are virtually maintained there; but it is sometimes necessary for them to be dealt with at the main works. In such cases they are taken as near as possible on the overhead gear and are towed for the remaining mile or so with booms anchored. Any manoeuvring is done on the batteries.

Now, as to the operational side of the company's business; my mentor was Mr. J. T E Robinson, A.M.Inst.T., the traffic manager. He briefly described to me the present set-up, as noted earlier. He further mentioned that the pool is administered by an advisory committee consisting of three members appointed by the company and three by the corporation, with a chairman and secretary from either side in alternate years Each side is responsible for the purchase and maintenance of its own plant, depots, fleets, staff, etc., but the corporation is responsible for the installation and maintenance of all fixed trolleybus equipment.

The company's average route mileage per month was about 340,000 during the war, but it has risen to 420,000 over the past 18 months, and is still increasing, as might be expected having regard to the housing developments. There is a seasonal fluctuation, naturally, and mileage figures are considerably influenced by the five-minute sea-front service in the summer, whereas only a light service is operated in winter.

War Casualties Light The Brighton and Hove transport system suffered less during the war years than many other undertakings. Fleet strength was maintained, a number of vehicles being hired to associated companies and to London Transport. Many old, skilled and trusted hands remained on the staff, and losses by enemy action were small. Several vehicles were damaged at various times, but there were no "write-offs." One garage was damaged and a driver killed while off duty.

The undertaking was, of course, ready for anything at crisis times, such as Dunkirk. It also dovetailed into a scheme with Eastbourne for relieving the Southern Railway when incidents caused disruption.

By the combined fleets, 100,000,000 passengers per year are carried. Of this figure, the company accounts for approximately 70,000,000. The morning peak is from 8.30 a.m. to 9 a.m., with a mid-day peak from 10.30 am to 3 p.m. (mainly shopping traffic). The worst peak is at 5.30 p.m., when shoppers, business Nople and entertainment seekers all crowd on to buses to return to homes, hotels or the railway station. There is also a sharp peak between 10.15 p.m, and 11 p.m., when places of entertainment discharge their patrons. In no case is there a real peak problem, such as Londoners know so well, but folk in Brighton and Hove consider a wait of two or three minutes an inconvenience. The morning peak, it is hoped, will be relieved by efforts—so far successful—which are being made to stagger the school hours All time-tables and publicity material are jointly organized by company and corporation, whilst to the public the system is in effect an entity. All vehicles are painted in the same mail-red and cream, with the exception . of the all-cream sea-front buses" All bear the name "Brighton, Hove and District Transport," but the corporation buses carry the Brighton coat of arms in addition.

Relieving Congestion ' One of the great problems which is successfully being overcome by the concern is that of congestion in what are left of the unusually narrow streets of Brighton. Recent efforts are in the way of properly co-ordinating bus stops, so that vehicles serving the same districts have common stops. Bus picking-up points are being marked out boldly in white to prevent motorists from parking on the stopping places.

A problem which remains unsolved is that of providing a direct north-south bUs route in Hove via The Drive, to connect with a new development area. The Drive is an ideal road, being one of the principal highways running direct from north to south, but it crosses the Southern Railway over a bridge plated to carry only two tons. In war-time it was plated by the Army authorities to carry 12 tons, yet permission cannot be obtained to run buses across it.

With regard to fare conditions, there are workmen's fares up to 8 a.m. at half the ordinary fare for single journeys, with a minimum of id., and according to a published scale for return journeys. There are children's and students' fares, but no special return fares for these classes. Penny fares are still obtainable and represent a large percentage of the total number of passengers.

Looking After the Staff Staff welfare is particularly good in the Brighton, Hove and District company In October last year an old office block was converted into a staff sports club. I saw the club and was most impressed by the equipment and decoration. All the work, I was told, was done by the men themselves in their own time, and a splendid job they made of it It was officially opened by the Mayor of Hove. Renee Houston and Donald Stpart attended as guests.

The club contains a billiards room, dance hall, bar (with darts, etc.), and lounge. Every Friday night is a dance night, and there are dancing classes on Thursday evening. Also among recreational facilities is a .22 rifle section. Subscription to the club is 3d. per week and it is self-maintaining. Staff dances are also held at Hove Town Hall and are frequently attended by well-known stage celebrities.

During the summer the sports club arranges visits into the country, when cricket matches are played with village teams, after which the "local" is visited for the darts contests. In the winter, village teams visit the' sports club for a social evening. There are still 18 conductresses in the company's employ. Two years ago there were 160. The assistance given by the women who came to the timely aid of the transport authorities has been much appreciated by the travelling public and the company.

Many of the drivers and conductors have served for long periods. Half a dozen have well over 40 years each to their credit, and 60 have over 25. well briefly to consider other factors which affect thermal efficiency.

As thermal efficiency is a measure of the amount of heat or fuel turned into power, an increase represents a direct gain either in power or fuel consumption, depending on which aspect the designer regards as the more important.

Thus, a high thermal efficiency is dependent on using the available fuel to the best advantage. In the case of a petrol engine, the principal factors are the type of fuel, the ratio of air to petrol, degree of turbulence, and efficiency of the ignition. In off in power. It has been suggested, recently, that detonation is a cause of increased cylinder wear.

Designers are now fully acquainted with the means for minimizing detonation. The fuel is the chief controlling factor, and, undoubtedly, the high compression ratios proposed on some new cars are.i anticipation of the availability of higher-octane patrols Fig. 3 shows the relationship between compression ratio and octane rating.

Commercial vehicle operators, with memories of the troubles caused by high-octane petrols in the late

As air alone is compressed, there is no theoretical limit to the compression ratio, the only difficulties being those connected with the necessity of providing adequate lift for the valves It must be borne in mind that an increase in the ratio means an increase in compression pressure and, consequently, a higher explosion pressure.

With egard to the compression pressure, this must be sufficient to raise the temperature of the air above the ignition point of the fuel. The ignition point of fuels is a, variable quantity, but it may be have ratios between 15 and 17 to 1, there being but few modern engines which exceed the latter ratio.

The answer lies in the maximum allowable pressure in the cylinder. As the maximum pressure increases, the strength and weight of the main engine structure must be increased in proportion. In fact, it is found that there is little improvement in fuel consumption by increasing the ratio beyond 14 to 1 Other factors, such as freedom from smoke, and a wider speed range, make the use of a ratio of, say, 16 to 1, desirable.

One of the principal problems in